There’s a famous economic law you may not have heard of, but it is valuable to understand.

It goes like this: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

It’s called Goodhart’s Law, named after British economist Charles Goodhart. He meant it as a warning to policymakers.

If you fixate too much on one data point – like inflation, test scores, or unemployment – you can end up distorting the very thing you’re trying to measure.

Here are ten relatable examples of Goodhart’s Law in action.

Think about the common thread. But fair warning: once you see them, you can’t un-see them. You’ll be prone to think of the incentives and structure behind every complex system you encounter:

- Soviet Nail Factory: When nail production was measured by weight, workers produced a few giant, useless nails. When the target changed to quantity, they made tiny, flimsy ones. In both cases, chasing the metric led to waste, not useful output.

- Central Bank Inflation Targeting: Central banks like the Fed focus on hitting a 2% inflation target. But this narrow focus has led to financial bubbles, rising debt, and asset inflation, while masking and exacerbating deeper problems in the economy.

- Standardized Testing in Education: Schools judged by test scores often “teach to the test” or even cheat. As a result, real learning declines, and education becomes more about gaming the system than teaching students to think. This is happening in AI Large Language Models (LLMs), too, where models are trained to hit certain benchmarks.

- Crime Statistics and Police Incentives: When police departments are rewarded for lower crime rates, they sometimes reclassify or underreport crimes. This improves the numbers on paper but hides real risks to public safety.

- CDO Risk Models and Pre-2008 Volatility Assumptions: In the years before the Global Financial Crisis, banks and ratings agencies used recent price volatility to estimate the risk of collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). Because volatility was low, the models assumed the assets were safe. But the low volatility was itself a product of the credit bubble, and when it cracked, the models failed catastrophically. Risk measures that became targets of design led to a systemic mispricing of danger. Using volatility as an input to risk models made the system much more fragile. The 2008 crisis only required a match. That match was falling house prices. In response to the financial crisis, the Fed went down the path of currency debasement – a path that has long-term consequences that still lie ahead.

- Volatility-Control Funds in the 2020s: Many modern funds adjust their exposure to stocks based on short-term volatility. When markets are calm, these funds pile into equities, pushing prices higher. But if volatility suddenly spikes, they’re forced to sell all at once, accelerating a downturn. By using volatility as both a measure and a trigger for action, they risk turning small shocks into major selloffs. This phenomenon heavily explains the algorithmic selling of stock indexes from April 2 to April 9, 2025.

- GDP Growth as a Sole Policy Goal: Governments pursue GDP growth through any means possible, including deficit spending and unsustainable development. GDP may rise, but quality of life, sustainability, and government-policy-induced wealth inequality are often ignored.

- Social Media Engagement Metrics: Platforms that reward content based on likes, shares, and comments have incentivized outrage, misinformation, and addictive behavior, distorting both public discourse and mental health.

- Academic Paper Counts: In academia, careers are built on the number of papers published. This encourages low-quality, repetitive research and discourages deeper, riskier work that takes more time but yields greater value.

- Corporate Earnings Targets: Companies chasing quarterly earnings goals may cut research, lay off workers, or engage in accounting tricks. They meet the numbers, but sacrifice long-term growth and innovation in the process.

Today, this warning embedded in Goodhart’s Law applies with alarming precision to the stock market.

The “measure” that’s been corrupted is the S&P 500 index itself.

The S&P 500 used to tell us something meaningful about the real economy. Today, it tells us more about the mechanical flow of retirement money than the health of American business.

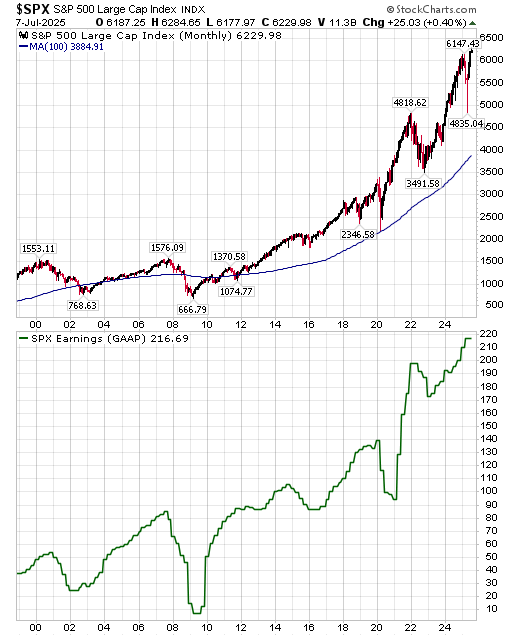

For long-term investors, this index does not offer much value relative to risk. It trades at 29 times earnings. It is far above a simple moving average (100-month, in blue). The SPY ETF which tracks the index pays a 1.1% dividend yield at a time when a 2-year Treasury note pays 3.9%. And the S&P 500’s earnings support, in green, is also far above its own trendline. The index’s GAAP earnings stream is vulnerable to the refinancing of its companies’ bonds at higher interest rates, plus lower profit margins in a slowing economy.

This shift didn’t happen overnight.

It’s the result of a long, slow move away from active investing and toward passive strategies. Instead of picking individual stocks, most investors now buy broad index funds, like those from Vanguard or BlackRock.

These funds don’t try to beat the market. They are the market. They buy stocks based on their size in the index, no questions asked.

On the surface, this passive revolution appears brilliant. Passive funds are cheap, with management fees close to zero. They have performed well in the past. And they require no effort.

But like so many financial innovations that seem too good to be true, this one comes with hidden risks that few investors understand.

According to Mike Green, chief strategist at Simplify Asset Management, this passive revolution has created unintended side effects that could end in disaster.

Green calls passive investing the “giant mindless robot.”

Why?

Because when new money flows into index funds, it doesn’t sit on the sidelines. This money flow is not completely isolated from the index it tracks. Rather, it buys stocks immediately. And not just any stocks. It allocates the largest share of incremental purchases to the largest stocks (like Apple, Microsoft, Nvidia, and Amazon) because those names dominate the index.

This creates what economists call a “price-insensitive buyer” – the most dangerous type of market participant. The money flows in, the big stocks get bigger, and the index rises. That rise draws in more money, which buys more shares, pushing prices even higher.

It’s momentum on autopilot.

Here’s where Goodhart’s Law reveals the fundamental problem. The index has become the target of trillions of dollars in retirement accounts, pensions, and ETF flows. It’s no longer as good a measure of economic strength as it once was!

But policymakers, journalists, and even many investors still treat it like it is. This creates a dangerous illusion that recalls the housing bubble’s false signals.

When markets rise, it looks like all is well. But the rise may have nothing to do with rising profits or productivity. It may simply be the result of mechanical buying by investors who have abdicated all responsibility for the deeper thinking that drives price discovery.

Consider the math of this distortion. Passive funds don’t care if stocks are expensive. They buy based on market cap, not fundamentals.

If Apple doubles in price, index funds buy more Apple. If Tesla triples, they buy three times as much Tesla as they did before it triples. Does that make logical sense? Not really – at least not to people who understand the history of large, bureaucratic companies and the law of large numbers. As long as prices are perceived to be on a permanent trend higher, few ask whether those companies are overvalued. This is like judging a company’s value by its popularity rather than its earnings potential.

Green explains that this creates a multiplier effect.

If you gave $1 to an old-school, active mutual fund manager, they might have sat on it, waiting for better stock prices or more favorable economic conditions. The market barely moves because back in the day, when value investing ruled, fund managers were liquidity providers and volatility dampeners. That is, when stocks went on sale, their demand for stocks rose. When stocks reached objectively expensive levels, they sold and raised cash.

But give that same $1 to a passive fund, and it gets deployed immediately into the biggest stocks. The impact that the marginal dollar has on stock prices when it goes to a passive fund is massive – up to 20 times greater than the same dollar going to an active fund, according to Green. A price-insensitive buyer is by definition not fazed by having a 20x impact on the marginal stock price.

Even worse, the larger passive funds get as a share of the total market, the more they will become volatility amplifiers. That is, passive fund inflows tend to rise as stock prices rise and slow as stock prices fall.

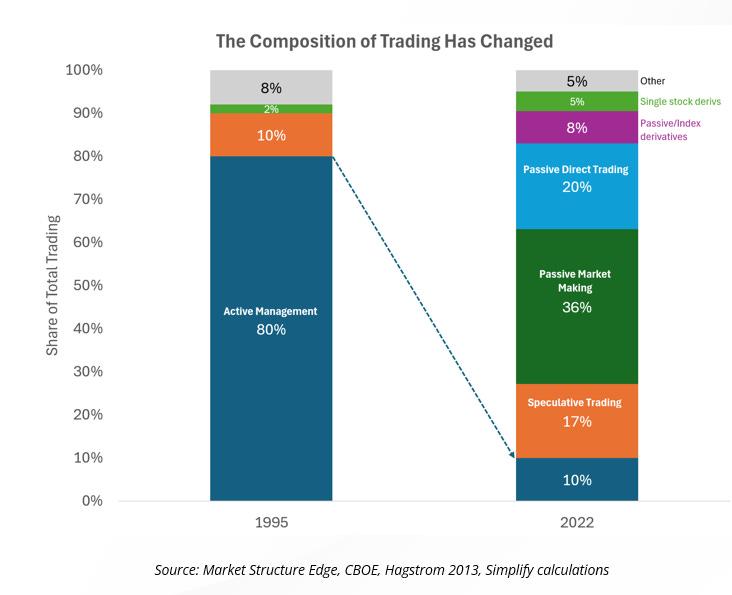

We haven’t seen a lengthy episode of passive outflows, but it’s daunting to imagine, especially with passive having become such a large component of the market. Green shows it in this chart of market structure evolution from 1995 to 2022:

A memorable insight from Green comes from a simple analogy he shared in a recent podcast interview with Thoughtful Money’s Adam Taggart, linked here.

Green asks us to imagine walking into a rug shop where the shopkeeper offers a Persian rug for $1,000.

A normal buyer might hesitate and start to walk away. The shopkeeper then says, “Okay, $500,” which entices the buyer. They perceive it as a bargain and decide to purchase.

Now, imagine how a passive fund would behave in the same scenario. Green explains: “The shopkeeper says, ‘$1,000,’ and they say, ‘Okay, I’ll take it.’ Then he says, ‘No, no $1,500,’ and they say, ‘I’ll take it.’ ‘$2,500?’ ‘I’ll take it.’”

This scene captures the absurdity of passive investing’s price-agnostic behavior. As Green notes, it’s not that passive funds are price insensitive. They’re actually price-responsive in the worst possible way.

“The next dollar that goes in rewards the stocks whose prices have already gone up,” he explains. Meanwhile, as the expensive “rug” gets more expensive, other investments that are becoming better long-term investments at lower prices get smaller in the index and receive fewer marginal dollars.

It’s a system that systematically reinforces momentum and punishes value. Green points out that even John Bogle, the father of index investing, misunderstood his own creation.

Bogle used to say investors should “ignore price.” But as Green notes, “What was your allocation mechanism? Price times shares outstanding, relative to price times shares outstanding for everything else. That is paying attention to price.”

In Green’s view, Bogle’s interpretation of his own method was “180 degrees wrong.” The index doesn’t ignore price – it slavishly follows price, buying more of what’s already expensive and less of what may have become cheap.

This is how the feedback loop forms, and why it’s so dangerous. Passive inflows drive prices up. Those rising prices attract more inflows. But what happens if the flows stop – or worse, reverse? That’s the nightmare scenario that keeps thinking investors awake at night.

The Fatal Flaw in the Machine

Passive funds are price-insensitive buyers. But they’re also price-insensitive sellers. When the selling begins, there will be no human judgment to moderate the process.

If investors start pulling money out of index funds (because of rising unemployment, mass retirements, or fear), those funds will be forced to sell. And they’ll sell without thinking. Other than maybe Warren Buffett in the twilight of his career, no analyst will broadcast a powerful enough second opinion to suggest, near the worst of a hypothetical future bear market, “Maybe this isn’t a good time to dump shares.”

It’s just sell, sell, sell – with the same mindless efficiency that drove prices up.

That could turn the feedback loop in reverse. Prices fall, which triggers more selling, which pushes prices down further. Calls for a more powerful force – say, the Fed? – to buy stocks will be deafening.

The Demographics Problem Nobody Wants to Discuss

One major, related issue is demographics. The math here is unforgiving. Baby Boomers hold most of the wealth in America. But they’re aging. At age 72, they must start withdrawing money from tax-deferred retirement accounts like IRAs. Some of that money gets reinvested. But much of it leaves the market altogether. This creates a steady, growing headwind for passive inflows.

At the same time, younger generations face economic headwinds that didn’t exist for their parents. Entry-level job prospects are weak. Wages are stagnant relative to asset prices. Many aren’t contributing to retirement plans at all. That limits the next generation’s ability to offset the Boomer outflows.

Green also warns in his interview that technological change is eating away at the job market faster than new jobs are being created. That means fewer workers, fewer contributions, and more early retirements – exactly the opposite of what passive investing requires to function.

In this environment, passive outflows are not a remote possibility. They’re a real and growing risk that most investors refuse to acknowledge.

The Illusion of Perpetual Returns

If and when these outflows arrive, the entire illusion could break. Investors have come to believe the S&P 500 will deliver 8% annual returns forever, almost as if this expectation is an unstated, unlegislated federal entitlement program. They observe past performance and make the faith-based leap to project the past endlessly into the future.

But that belief ignores the distortions baked into the market.

It ignores how passive flows inflate prices. It ignores how market cap weighting favors the already big. It ignores how the index is no longer a tool of discovery, but a target of blind capital. In other words, it ignores Goodhart’s Law.

Preparing for What Comes Next

Markets are not miracles. They reflect human decisions, or lack thereof. When the majority investing strategy becomes “just buy the index,” the system becomes fragile. It works as long as the flows are one way, into index funds. But history teaches us that trends never last forever.

This isn’t a call to panic. But it is a call to think – and to prepare. The passive bubble may not pop tomorrow. But it’s built on assumptions that can’t hold forever. One of those assumptions is that indexes still tell us the truth about real, sustainable value creation in Corporate America. Goodhart’s Law says they don’t. And when the flows eventually turn, the truth will hit with the force of mathematical inevitability.