By Richard Walker

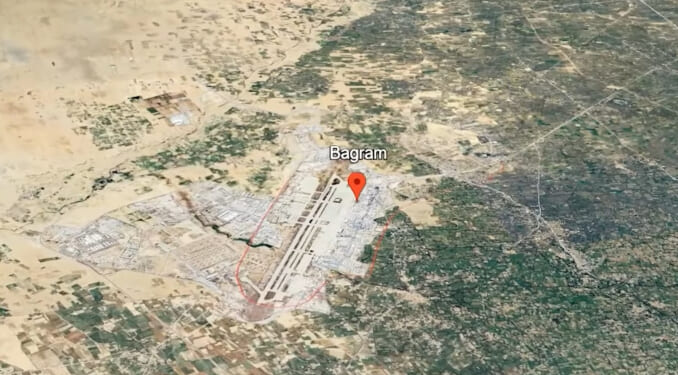

President Donald Trump’s request to the Taliban to let him have the massive Bagram air base that featured prominently during the Afghan War was rejected, but it signaled a renewed focus on a country America left in a very messy exit, and exposed business dealings with Pakistan.

Click the Link Below to Listen to the Audio of this Article

The Biden administration’s pull-out from Afghanistan was such an unmitigated disaster that the United States left behind enough modern weaponry to equip an army. Some of those weapons have since found their way into the hands of Taliban-linked groups trying to destabilize nuclear-armed Pakistan.

To make matters worse, the Taliban has been tracking down Afghan special forces personnel who worked with British and U.S. teams during the war. Many of those Afghan soldiers have been tortured and executed, having been denied visas to flee with their families to Britain and America. Sadly, their plight has not been brought to the attention of the U.S. and British public.

Simplistically, the only possible reasons that Trump would seek to re-populate the Bagram base with U.S. military personnel and hardware is because intel suggests Afghanistan has the potential to become a new hotbed of anti-Western extremism. Others say it is because Pakistan appealed to Trump to help in its fight to counter jihadist forces flowing over the border from Afghanistan into northern Pakistan to kill soldiers and police.

Pakistan, a close ally of Saudi Arabia, has built ties to China that Trump would like to sever, but that may not be easy. In the meantime, Pakistan’s nemesis, India, has seen the Trump swivel toward Pakistan as a betrayal. It has thus moved closer to China and Russia.

The rebuilding of ties between Islamabad and Washington began recently and surprised many, given that Trump, in his first term, cut massive U.S. aid to the Pakistan military for not doing enough to counter terrorism from Afghanistan.

His latest focus on Pakistan was self-evident when he invited Pakistani Field Marshal Asim Munir to the White House in June, without any diplomats present. It was a first for a Pakistani leader and was followed on Oct. 25 by another White House get-together with Munir and Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif. Trump has described Munir as his “favorite general.”

On its face, this was a budding relationship in which Pakistan and the United States could forge an alliance against Islamist militants backed by the Taliban, if not the Taliban itself. There were, it soon transpired, other elements at play.

First, Pakistan, not India, supported Trump’s claim that he recently prevented a potential war between the nuclear nations.

That pleased Trump, as did Pakistan’s two public calls for him to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Little mention was made about the fact that Pakistan and Afghanistan hold some of the largest reserves of rare earth minerals needed by the United States for its military-industrial complex.

But it was not long before India began to suggest that it knew of other motives for the radical shift in U.S. policy toward Pakistan.

India, much like other nations, had already determined that Trump policymaking has a transactional element, sometimes shaped by personal animus, or financial interests. The Hindustan Times was not long in reminding its readers how Trump, on Jan. 1, 2018, claimed the United States had foolishly given Pakistan $33 billion over 15 years, and all it got in return was “nothing but lies and deceit.”

Indian commentators, and others elsewhere, began to zero in on Trump’s interest in rare earths because China, which holds the largest reserves of rare-earth minerals, was limiting their export. But another factor soon found its way into the public analysis.

The Hindustan Times pointed to Trump family ties to Pakistan’s military—which has long been in the business of making large profits from personal projects.

In April, World Liberty Financial, in which Trump’s sons Don and Eric, and son-in-law Jared Kushner, have a 60% share, inked a major agreement of intent with a newly created Pakistan Crypto Council run by members of Pakistan’s military.

Other White House deals related to natural resources followed, involving U.S. companies and ones tied to “milbus,” as in military business; a term the Pakistan military acquired from a controversial book published in 2007 by Dr. Ayesha Siddiqa. He reckoned back then that the Pakistan military’s “milbus” had a personal worth of more than $20 billion.

India has, of course, personal motives for blackening Trump’s about face on Pakistan, but it is not exactly clear what the outcome will be, and whether Trump will be able to press the Taliban to let him have Bagram air base.

The prospect of a return to Afghanistan might not, however, sit well with America firsters. Nevertheless, the need for minerals required for ballistic missiles and satellites could be at the core of the sudden interest in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

For example, China knows that as much a $6 trillion in rare earth deposits are in the Baluchistan area of Pakistan, a troubled part of the country. Others see this realignment as a message to India that it is not indispensable to U.S. strategic foreign policy interests.

India’s cooling off in regard to its ties with Washington, and its refusal to stop buying Russian oil, angered Trump, who believed he had good relations with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

The sudden love affair with Pakistan carries risks if it so isolates India that it ends up in a deeper embrace with China and Russia, weakening in the process its role within the Western alliance in the Asia Pacific region.

Just like the negative impact of the Joe Biden family in its forging of business deals linked to U.S. foreign policy, Trump risks even more with a family that sees no downside in exploiting the power and influence of the presidency for personal financial gain.