Every so often, Wall Street rediscovers something that’s been sitting in plain sight for years. Right now, it’s rediscovering the American consumer. Specifically, the consumer is leveraged to the hilt, running out of oxygen, and basically holding up 70% of the U.S. economy with a credit card that’s already maxed out.

And the craziest part? Most people think we’re safer because housing isn’t blowing up like it did in 2008. And they’re right… sort of. Mortgages aren’t the problem this time.

But everywhere else, the homeowner is in danger.

The shift doesn’t show up in the usual headlines. It hides in the fine print of bank disclosures, the rising APRs on your neighbor’s Visa bill, and the buttock-clenching desperation of people rolling over their balances because they have no other option.

The new risk is a slow-motion suffocation of the very people who are the economy.

Welcome to Consumer Credit World, where everything looks fine until it doesn’t.

From McMansions to Maxed Out Cards

Pre-2008, household leverage was all about the house. Mortgages were too big, underwriting was too loose, and too many people bought homes they had no business owning. In short, there were way too many American NINJAs! (Remember: “No Income, No Job, and no Assets.”)

When prices rolled over, the whole system detonated. As a result, we got all sorts of nonsense like negative equity, foreclosures, job losses, and a lending environment so frozen you assumed your mother-in-law kissed it.

After that catastrophe, households did something unusual. They deleveraged. Really.

Mortgage debt-to-GDP fell. Bankers stopped writing mortgages on cocktail napkins for their favorite stripper. FICO scores went up. Fixed-rate mortgages took over. And for the first time in 30 years, people didn’t look like pent-up prisoners in their own living rooms.

But while everyone was celebrating the newfound prudence (their word, not mine) of the American household, something subtler happened. The leverage didn’t vanish. It migrated.

Credit cards. Auto loans. Personal loans. Buy-now-pay-later. Student debt that can’t be discharged in a bankruptcy. That’s the real U.S. consumer balance sheet, and today it’s heavier — relative to incomes and GDP — than it was in 2007.

Worse, unlike mortgages, this debt is short-term, expensive, and aggressively repriced. A 30-year mortgage at 3% barely notices the Fed. A credit card at 29% makes the holder quake at the very mention of a rate hike.

And unlike a house, you can’t live inside your MasterCard bill.

This is why the next squeeze won’t look like 2008. It’ll look like a middle-class cash-flow crisis.

Why Consumer Debt Hurts Faster — and Harder

Let’s say you borrowed $20,000. On a mortgage at 4%, that’s barely dinner money. On a credit card at 28%, it’s a financial hemorrhage. And as the Fed hiked rates at record speed, those credit card rates shot up instantly.

Millions of households were insulated from higher mortgage rates — but there’s no escape from credit card APRs.

It’s a monthly squeeze, not a sudden catastrophe. Miss a mortgage payment, and you may get 90 days of wiggle room. Miss a credit-card payment, and your credit score face-plants immediately.

That pressure flows directly into discretionary spending — the exact slice of the economy that reacts most quickly to a recession. Restaurants, travel, retail, electronics, hotels, online shopping… all of them rely on the very dollars that are now being siphoned off into interest payments.

This is why credit stress is such a vicious early-cycle indicator. It hits the weakest households first, chokes off spending second, and only then shows up in the broader economic data.

By the time the charts look ugly, consumers have already been living through the slowdown for 6 months.

A 70% Consumption Economy Built on Sand

Here’s the part policymakers never say out loud: the U.S. economy is basically a giant Ouroboros of consumer spending. Seventy percent of GDP is personal consumption. Meaning: if households even sneeze, the economy catches pneumonia.

And right now, the sneeze is more like a cough.

High consumer-credit balances mean yesterday’s purchases are devouring more of today’s income. Think of it as a shadow tax… except it rises automatically with interest rates and never gets voted on.

Already squeezed by inflation, lower-income households feel it first. But the middle class isn’t far behind. The effect is subtle at first: a staycation here, a used car there, switching from Whole Foods to Walmart, putting off dental work, delaying home renovations.

And then one day it isn’t subtle at all.

The industries that depend on discretionary dollars — apparel, travel, home goods, entertainment, leisure, restaurants — suddenly see revenue slow. CFOs cut hiring plans. Overtime disappears. And the labor market suddenly looks mortal.

That’s when defaults pick up. That’s when lenders tighten standards. That’s when the feedback loop begins.

And once that loop starts, it’s tough to stop.

The Fed Didn’t Realize It Changed the Machine

The current monetary policy was designed in a world where mortgage debt was the primary transmission channel. The Fed raises rates, and mortgage resets choke off housing. The Fed lowers rates, and then refinancing revives demand.

Clean. Predictable. Neat.

That machine is gone.

Today, when the Fed hikes, mortgages barely flinch. Instead, the pain lands squarely on credit cards and auto loans, where APRs reset with lethal speed.

This is why Powell’s aggressive tightening cycle in 2022–2024 produced such a strange economy. Housing didn’t break. Banks didn’t break. But the consumer started wheezing… slowly at first, then more loudly each quarter.

Now inflation has cooled, unemployment is drifting up, and the Fed has started cutting. But here’s the catch: cutting rates merely reduces the rate of bleeding. It doesn’t reverse the fact that households are carrying the highest level of non-mortgage consumer debt in history.

Rate cuts won’t turn a 29% APR into something pleasant. They’ll just make it 25%.

The debt, stress, and fragility remain.

Forget “Systemic Housing Crisis.” Think Rolling Consumer-Credit Shocks.

The good news? A 2008-style collapse is highly improbable. Mortgage underwriting is tight, bank capital is better, and there’s no giant pool of toxic MBS waiting to implode.

The bad news? The system can still suffer, just in a different way.

History doesn’t repeat, but it rhymes… and sometimes, not very well.

Instead of one giant detonation, we’ll get rolling mini-crises in consumer credit. Delinquencies rise in credit cards first. Auto loans follow. Personal loans next. Lower-income households get hit first, then the middle of the distribution.

Jay Powell, or his successor, will feel like he’s walking through an economic minefield.

As credit quality worsens, lenders pull back. There goes your liquidity. That hurts the very consumers who rely on credit to smooth income volatility. Then, spending falls harder. Job losses accelerate in consumer-facing industries. That produces more delinquencies.

It’s the same doom loop, but it’ll be coming from a different corner of the balance sheet.

Call it “2008, but diffused.” It’ll be quieter and slower, but still capable of dragging the economy into recession.

Why Policymakers Are Cornered

This situation creates a predicament for the Fed and Treasury. Or did they create it?

On paper, household debt-to-GDP looks fine. But once you dig into the distribution, you see the fragility: millions of households with almost no liquidity buffer and double-digit interest obligations.

That cornered the Fed during its tightening cycle. It will corner the Fed again next time.

Raise rates? You crush the consumer immediately.

Cut rates? You validate the behavior that created the stress in the first place.

It’s monetary whack-a-mole, and Powell has only one hammer.

And remember, the U.S. political system loves consumer credit. It props up spending. It props up GDP. It props up elections.

So don’t expect Congress to do anything but cheer more lending.

That’ll leave us with the same fragile equilibrium we’ve been drifting toward for a decade: an economy powered by consumers who can barely afford to consume.

Where This Leaves You and the Markets

For investors, this new credit regime changes the signals you watch.

The next recession isn’t coming from collapsing home prices. It’s coming from rising delinquencies in unsecured credit. Watch credit-card charge-offs. Watch auto-loan stress. Watch the spreads in consumer ABS.

Those will turn before non-farm payrolls do.

Consumer-facing stocks — retail, travel, restaurants, leisure, discretionary goods — are the new canaries in the financial coalmine. The stock prices of banks with heavy unsecured exposure will be far more volatile through the cycle.

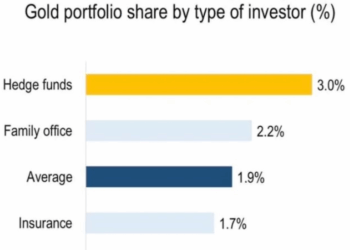

But commodities? Precious metals? Real assets? They tend to love environments that force the Fed to pivot early because the consumer is buckling.

After three straight rate cuts and an announcement that the Fed will be buying $40 billion of Scott Bessent’s T-Bills forthwith, I suspect we’re already in that very environment.

Wrap Up

Yes, homeowners are safer today. Yes, banks are better capitalized. No, we’re not replaying 2008.

But don’t confuse that with stability.

Debt didn’t leave the system. It migrated into a more fragile, more expensive, more interest-sensitive part of the household balance sheet. And like a giant pesky leech, it has attached itself to the engine of the entire economy.

That’s why the next downturn won’t be about houses.

It’ll be about people.

The consumer is the business cycle. And for the first time in a while, the consumer looks tired.

Very tired.