Among the orders issued as Union troops arrived in Texas at the end of the Civil War was one declaring that all enslaved people in the state were now free, and had “absolute equality.”

General Order No. 3 — issued when U.S. Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger and his troops landed in Galveston on June 19, 1865 — is the genesis of the Juneteenth celebrations marking the end of slavery in the U.S.

Word spread across Texas, a Confederate state that had only surrendered weeks earlier, as troops posted handbills of the orders, and newspapers published them. The only one of those handbills still known to exist resides at the Dallas Historical Society, where it will be on display from June 19 through October. 19.

She said people would dress up and go to a public place like a park or a church to celebrate.

“There’d be barbecue and celebrations,” Hopkins said. “It was really an effort for people to say: Look at how far we’ve come. Look at what we’ve been able to endure as a community.”

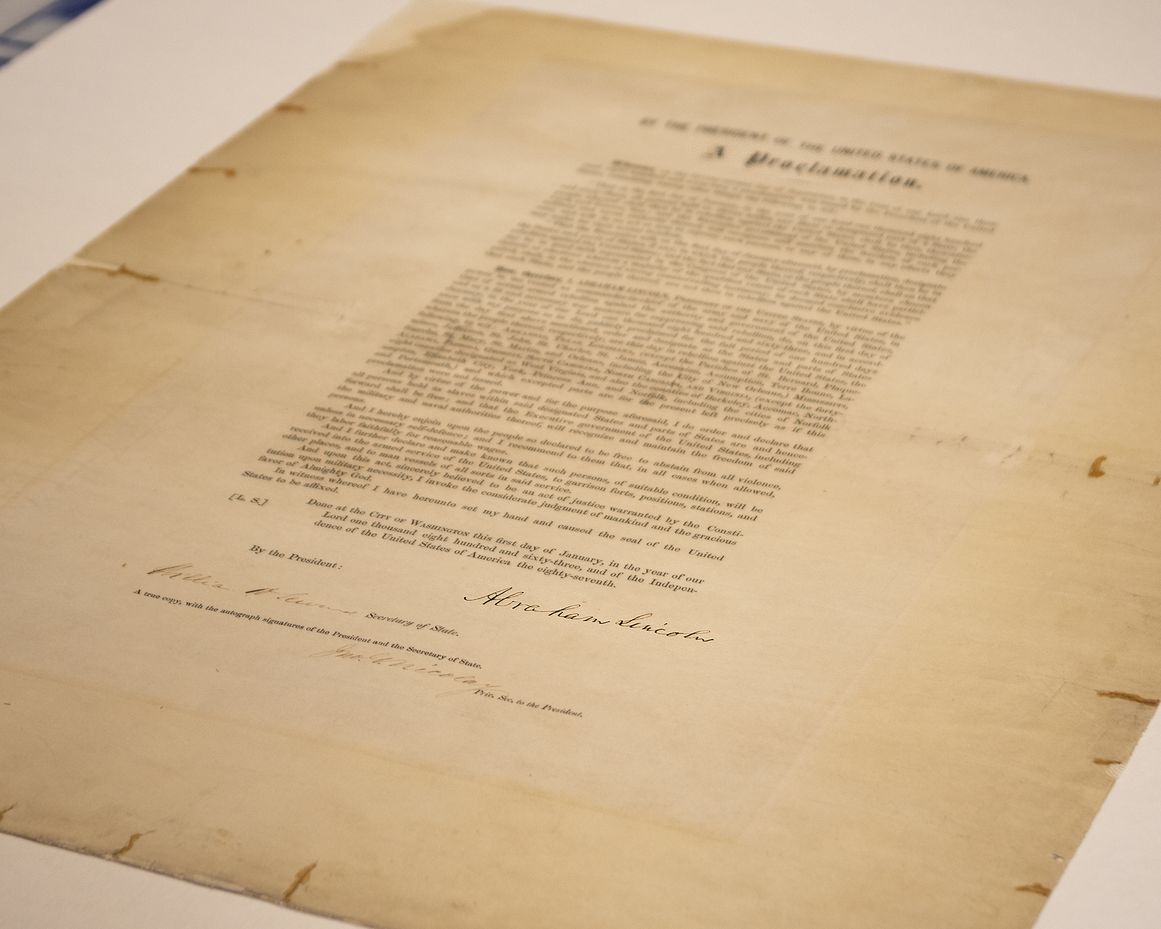

Progression of freedom On Jan. 1, 1863, nearly three years into the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared the freedom of “all persons held as slaves” in the states still within the Confederacy. But that didn’t mean immediate freedom.

“It would take the Union armies moving through the South and effectively freeing those people for that to come to pass,” said Ed Cotham, a historian wrote the book “Juneteenth: The Story Behind the Celebration.”

The proclamation also didn’t apply to the border states, which allowed enslavement but didn’t leave the Union, nor those in states occupied by the Union at that time, said Erin Stewart Mauldin, chair of southern history at the University of South Florida in St. Petersburg.

“You have to think of emancipation as a patchwork,” she said. “It doesn’t happen all at once. It is hyperlocal.”

Still, she said, the proclamation “was recognized immediately as this watershed moment in history.”

“The Emancipation Proclamation is the promise that the end of slavery is now a war aim,” Mauldin said.

The 13th Amendment abolishing slavery in the U.S. was ratified on Dec. 6, 1865.

Texas at the end of the war

As the war progressed, many enslavers from the South had fled to Texas with their enslaved people. So the enslaved population in Texas grew from about 182,000 in 1860 to about 250,000 at the end of the war in 1865, Mauldin said.

Cotham said that while enslaved people were emancipated “on a lot of different dates in a lot of different places across the country,” one reason that makes Juneteenth the most appropriate holiday to celebrate the end of slavery is that it represents the last “last large intact body of enslaved people to be freed at the end of the war.”

Many enslaved people would have known about the Emancipation Proclamation and known that the end of the war would mean freedom, experts say.

“We know that there was a very, very effective informal communication network between the enslaved people all across the South and particularly in Texas,” Cotham said.

The proclamation, he said, didn’t mean anything in Texas without armed troops arriving who “were determined to enforce emancipation.”

General Order No. 3

The new orders under Granger were printed in newspapers and handbills were pasted around the state.

“All the Union troops took copies of it and pasted it and posted it and read it as they went all through Texas,” Cotham said.

On the handbill, General Order No. 3 freeing the enslaved in Texas was one of four military orders listed, including orders stating Granger’s authority and stating that Texas actions since succession were nullified.

General Order No. 3 begins by informing the people of Texas that “all slaves are free.” “This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor,” it reads.

The order then goes on to advise freedmen to “remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages,” adding that they “will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

Mauldin said the back half of the orders say, in essence, “stay where you are, we’re going to figure this out,” which became the purpose of the federal government’s Freedman’s Bureau.

Portia D. Hopkins, Rice University’s historian, said that while there was excitement, the newly freed people knew they had to “build up what citizenship looked like for them.”

“The wages that they were supposed to be paid ended up being another form of exploitation with sharecropping,” Hopkins said.

The only known surviving handbill was part of the collection of newspaperman George Bannerman Dealey, who founded the Dallas Historical Society. He began working at the Galveston newspaper in 1874, and was appointed business manager of The Dallas Morning News when it was founded in 1885.

“As far as we know, there’s not another copy of that out there because people threw them away. You post them on a pole or you post them in a post office .. but after they are done people don’t usually keep these things,” said Karl Chiao, executive director of Dallas Historical Society.

Tommie D. Boudreaux, who is part of the Galveston Historical Foundation’s African American heritage committee, said that according to the newspaper, the order was posted in Galveston at the Custom House, the court house, in the downtown area known as the Strand, and at Reedy Chapel.

“Some of the people who were set free stayed on the plantations and worked for their former owners, others left, they went to Houston, to Dallas, or the went to San Antonio seeking work, and seeking to get as far away from their masters and former owners as possible,” said W. Marvin Delaney, deputy director of the African American Museum of Fair Park in Dallas.

Juneteenth celebrations

Juneteenth became a federal holiday in the U.S. in 2021 but it began being celebrated in Texas the next year, and as time passed, communities outside of the state also began marking the day.

“You started to see community celebrations in places all over the South,” Hopkins said. “In part because people are coming from Texas, people are migrating and moving. But also in part because Black people are recognizing that this represents not just the end of enslavement but the beginning of a new chapter for Black people in America.”

Mauldin said that those early celebrations were “not only a huge signifier that something had changed, of a revolution happening” but also showed incredible bravery “these people gathered in public to celebrate their freedom under constant threat of violence.” And that, she said, was especially true once the Ku Klux Klan was established in Texas in 1868.

“It does take time for sort of what freedom is going to look like to be made real and in large part the reason that freedom is made real is because of ex-slaves pushing for what they think freedom should be,” Mauldin said. “It’s not being given to them, they are actively fighting for it.”