By José Niño

The Netherlands has thrust itself into the epicenter of the global chip war. On Sept. 30, the Dutch government invoked the Goods Availability Act—a Cold War relic rarely used in peacetime—to seize operational control of Nexperia, a semiconductor firm based in Nijmegen, Netherlands, but owned by China’s Wingtech Technology.

Click the Link Below to Listen to the Audio of this Article

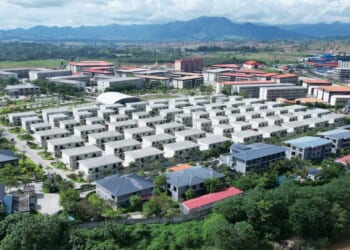

Nexperia, born decades ago out of Philips NV Corporation’s storied semiconductor division, now finds itself the subject of intense scrutiny. While few in the Netherlands realize the extent of their reliance on its chips—a commodity present in cars, phones, and industrial machinery—Nexperia’s true global footprint has long outstripped its domestic one. Only 400 of its 12,500 employees work in the Netherlands. Its manufacturing empire stretches across Germany, the United Kingdom, Malaysia, the Philippines, and, crucially, China, where most of its 100 billion chips are completed each year.

Real problems drove the government to intervene, not just hypothetical risks. The Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs cited “serious governance shortcomings,” saying these threatened “the continuity and safeguarding on Dutch and European soil of crucial technological knowledge and capabilities.”

Court records revealed worrying conduct by chief executive Zhang Xuezheng, Wingtech’s founder. Zhang allegedly forced Nexperia into ordering $200 million worth of silicon wafers from his private firm, despite only needing $70–$80 million. Additionally, he planned to discard the surplus.

With the Goods Availability Act, Economic Affairs Minister Vincent Karremans gained authority to override or block Nexperia decisions threatening Dutch or European interests. Zhang was promptly suspended as CEO and director, and his voting rights reassigned to an independent court-appointed administrator. CFO Stefan Tilger assumed interim command.

Geopolitical forces added hostility to this narrative. In late September, the U.S. Commerce Department broadened its “entity list” sanctions, catching Nexperia in the crossfire as a wholly owned Wingtech subsidiary. Board minutes from a June meeting made clear Washington’s expectations: “The fact that the company’s CEO is still the same Chinese owner is problematic. … It is almost certain that the CEO will have to be replaced” for Nexperia to avoid U.S. sanctions. Wingtech’s presence on the entity list, dating from December 2024, had already made American technology exports to Nexperia all but impossible.

Beijing moved next. On Oct. 4, China’s Ministry of Commerce imposed export controls that prohibit Nexperia China and its contractors from shipping key chip components abroad. The blow landed hardest in Dongguan, China, where Nexperia’s massive packaging plant handles roughly 70% of the firm’s finished shipments.

European carmakers like BMW are scrambling for risk assessments, as their supply networks have already been impacted by the dispute.

Chinese officials did not hide their aggravation. Foreign Ministry spokeswoman He Yongqian declared, “China firmly opposes the Dutch side’s attempt to expand the concept of national security and directly interfere in the internal affairs of enterprises.” He added that the intervention “not only violates the spirit of contractual agreements and market principles, but will also severely damage the Dutch business environment.” The Global Times labeled the move “predatory” and “serious harassment.”

Such rhetoric has not silenced critics within Europe. The Financial Times observed, “Europe is still too dependent on Chinese supply chains. An open technological war could do more harm to us than to them.”

The grim arithmetic is clear. While Nexperia’s intellectual property and brand reside in Europe, its physical output depends mostly on China. The firm now sits between two regulatory regimes, unable to receive U.S. technology and unable to export its Chinese-manufactured goods.

The Nexperia episode is not Europe’s first brush with hardware vulnerability. In 2022, the United Kingdom forced Nexperia to divest most of its Newport Wafer Fab shareholding, citing national security fears. Malcolm Penn, a former Newport board member, accused Nexperia’s Chinese parent of “hostile takeover” tactics, noting China’s capacity for scale and its determination to centralize production.

Now, as Karremans and his team seek a path forward, they must balance corporate continuity with national security, and economic recovery with technical independence. Dutch blog “Hollands Welvaren” noted:

It is now up to the Dutch government, the court appointed director, and other remaining Nexperia board members to fix this problem. At stake is not just the future of Nexperia, but also of the Dutch semiconductor cluster—Europe’s most important.

The saga is a lesson on the delicate position of middle powers caught between superpowers, forced to navigate not only the tides of technology but also the tempests of geopolitics. Uncertainty persists, but the Nexperia story stands as warning and a parable, a testament to the new world where technology and sovereignty collide, and where every microchip is a pawn on the world stage.

José Niño is a freelance writer based in Austin, Texas. You can contact him via Facebook and Twitter. Get his e-book, The 10 Myths of Gun Control at josealbertonino.gumroad.com. Subscribe to his “Substack” newsletter by visiting “Jose Nino Unfiltered” on Substack.com.

(function() {

var zergnet = document.createElement(‘script’);

zergnet.type=”text/javascript”; zergnet.async = true;

zergnet.src = (document.location.protocol == “https:” ? “https:” : “http:”) + ‘//www.zergnet.com/zerg.js?id=88892’;

var znscr = document.getElementsByTagName(‘script’)[0];

znscr.parentNode.insertBefore(zergnet, znscr);

})();