In 1929, just before the Great Crash, economist Irving Fisher famously said stock prices had reached, “what looks like a permanently high plateau”.

Fisher was a raging bull, and his portfolio was leveraged to the hilt. The crash wiped out his entire fortune, and he was forced to borrow from wealthy relatives to pay his IRS bill.

It’d be easy to scoff at his arrogance. But Fisher’s view was mainstream at the time.

And in some ways, there was justification for the widespread optimism.

The 1920s were a period of incredible technological advances. It was the decade when electric power matured in industry and households.

Electricity caused productivity to soar. In 1914, about 30% of factories ran on electricity. By 1929 it was up to 78%.

The new tech was a massive upgrade from steam power. Cheaper, safer, cleaner, and far more productive.

So investors had good reason to be bullish. It seemed like the beginning of a new era.

The breakthroughs were real. But unfortunately, human nature got in the way.

Off the Rails

Utilities borrowed heavily and built too much electrical capacity. Industrial giants like GM and Ford also got ahead of themselves, building too much new infrastructure too quickly.

Investors abused margin, often utilizing 10x leverage. They crowded into speculative trades.

Shady operators rushed to start new electric and radio businesses, fueling a cycle of bad investments.

The Federal Reserve helped fuel the bubble, lowering interest rates and printing money.

It was a classic speculative mania. Started by real technological breakthroughs, and fueled by mania, bad actors, and reckless monetary policy.

We saw the same playbook in the dotcom mania of the 1990s (more on that here).

Will the current AI mania face the same fate?

A Bubble of Our Own

The Wall Street Journal just published a new piece on this very topic. Two of the charts are worth reviewing.

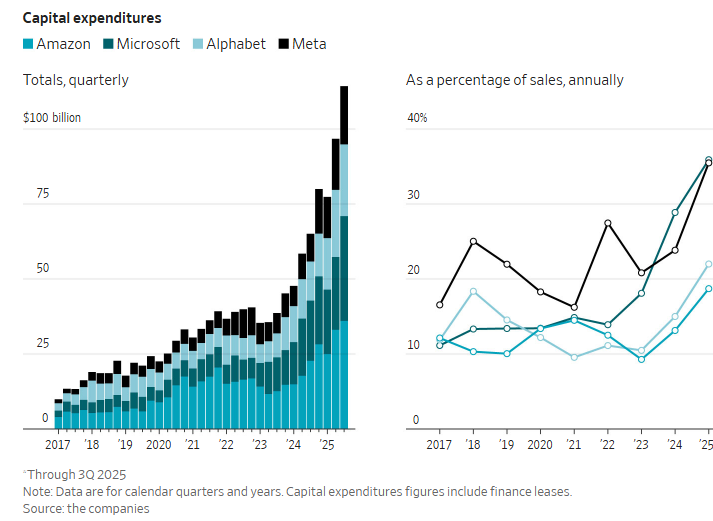

First up, a chart of quarterly capital expenditure (capex) investment by Amazon, Microsoft, Alphabet (Google) and Meta (Facebook). This capex is mostly on new GPUs, servers, and data centers.

In the left panel, we see how dramatically big tech’s capex is growing.

However, revenue is growing too. So on the right side, we see spending as a percentage of revenue. Even as a percentage of revenue, big tech spending is extreme.

Meta is now spending about 36% of revenue on capex. Microsoft is around the same level, while Amazon and Alphabet are “only” spending about 20% of revenue.

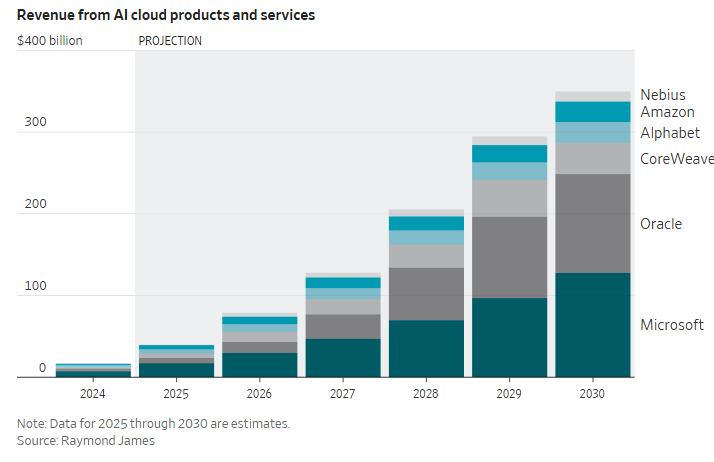

The biggest companies in the world are betting big on an AI-centric future. Here’s another chart from the WSJ piece, showing AI revenue projections.

As you can see, 2025 AI revenue from these 6 big players is estimated to be around $30 billion this year.

By 2030, just 5 years away, sales are expected to jump to $350 billion. So Wall Street is looking for 11x growth in 5 years. Those are some peachy projections.

And here is some accompanying commentary on the AI hype, via the WSJ:

Recently, analysts at JPMorgan Fundamental Research created a financial model that projects total investment in global AI infrastructure through 2030, taking physical limitations into account. That figure is $5 trillion.

Then they calculated how much new revenue these companies will have to generate to justify that $5 trillion investment in AI supercomputers. The result: AI products would have to create an additional $650 billion a year, indefinitely, to give investors a reasonable 10% annual return. That’s more than 150% of Apple’s yearly revenue, and a far cry from OpenAI’s current revenue of about $20 billion a year.

This equates to every iPhone owner in the world paying an extra $35 or so a month for products and subscriptions, according to the JPMorgan analysts.

Cheap Chinese AI Models Throw a Wrench

Big tech is investing massively on the assumption that AI spending is going to skyrocket over coming years.

This means that the big American models, like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude, need to win a huge amount of new business.

But cheap open source models from China are mucking up this assumption. The Economist reports that leading venture capital firm a16z says 80% of startups they talk to are running Chinese AI models like DeepSeek or Alibaba’s Qwen series.

Most Chinese models are open source, meaning they’re free to use and modify. Top American models can be 10x more expensive.

Former Google CEO Eric Schmidt is worried that governments around the world will gravitate towards these models due to much lower costs, and the ability to customize them. Here’s Schmidt via Business Insider:

“So the vast majority of governments and countries who don’t have the kind of money that the West does will end up standardizing on Chinese models not because they’re better, but because they’re free.”

If these open source Chinese AI models continue to improve, there is a risk that they will win over many companies, and even global governments. If the economy takes a turn for the worse, this risk gets bigger.

Then all that capex by American big tech could prove to be wasteful.

Chinese models gaining ground is just one potential black swan that could pop the AI bubble. A few weeks back, we discussed the possibility of an AI efficiency breakthrough that could make such massive infrastructure spending unnecessary.

We also are facing an ongoing electricity squeeze here in the U.S. There’s not enough power for all the data centers companies want to build.

So I’d say that over the next few years, there are a few different paths we could go down where the bubble pops in an unpleasant fashion.

And besides these fundamental factors, we also need to keep human nature in mind. Our brains aren’t designed for trading, especially during a bubble. So we have a tendency to get caught up in the moment. This type of mania is very difficult to resist.

My advice is to take some profits if you’ve got’em, and begin diversifying into precious metals and hard assets if you haven’t yet.

When this current mania ends, it could take a decade or longer for the tech sector to recover.