In recent news, oil giant Chevron announced that this year and into 2026, it will lay off between 15% and 20% of its workforce, including geological, engineering and other related scientific and technical personnel. The company states that it must cut costs and simplify operations.

Meanwhile, Chevron also announced that it will scale back its share buyback program, although the dividend is supposedly safe for now.

When a big oil company lays off technical people to “save money,” as the saying goes, it means that something is going on and it’s probably not good. Perhaps the issues are purely internal to Chevron, or perhaps Chevron reflects larger problems across the oil patch.

With this in mind, today we’ll discuss several general issues about oil, oil prices, price trends, what it all might mean, and how to play it as an investor. That is… What’s going on with oil? And more specifically, what’s in it for you if you care to act?

Seasonality, or More?

It’s early May and winter has ended in the Northern Hemisphere, other than up in a few still-frozen northern regions of, say, Canada or Northern Europe. All across Asia, Europe and North America, the heating season is over and summer driving season is kicking in.

With this in mind, it’s worth noting that the price of a barrel of crude oil began this week in the $57 range on the New York Mercantile Exchange. As you can see from the following chart, this price is relatively low by recent standards, in fact around a four-year low:

NY Mercantile chart, past 5 years; Yahoo Finance.

Also from the chart, look back to 2020 – 21 when we had low oil prices during those sweeping COVID-lockdowns, and much of the global economy ground to a halt. In other words, oil demand was down in that time period, as were oil prices. And at root, it was all basic economics at work: supply and demand.

Okay, so that was then, in 2021. What’s happening now, today? Why are oil prices revisiting previous lows? Is there a pandemic somewhere and nobody published the news? Again, let’s return to that price chart.

In mid-2022 oil prices spiked up, mostly due to fears of global shortages related to Russia’s move into Ukraine back then. Many people believed that anti-Russian sanctions would remove a large whack of global supply, and shortages would support higher prices. But no, that’s not what happened.

As 2022 unfolded, the predicted oil shortages never materialized. Instead of halting oil exports to Europe, at least some Russian oil continued to move West, sanctions or not. Europeans are fickle and self-interested like that.

Meanwhile, Russia increased oil exports to China, India and other countries that cared little for Western protocols. Indeed, India rapidly built out a very profitable refining sector devoted to buying Russian oil at a relative discount, processing it, and then exporting final products to Europe at handsome, marked-up world price levels.

Broadly speaking, global oil output has been ample for the past couple of years. The only real issue has been logistics, meaning which tankers were permitted to load or unload in what ports, so as to dodge sanctions and avoid or evade Western legal process.

One way or another, since 2022 the world has never experienced any true oil shortages, and thus have prices stabilized and even retreated.

Also per the chart above, note how in mid-2024 oil prices began another swoon; and this was long before Donald Trump won the presidency last November, let alone took office in January of this year. The point is to show how, for about three years, oil prices have followed a generally declining trend. Price-wise, Mr. Trump didn’t matter and this was a global trend.

Meanwhile, in this regard it begins to make more sense that even a large company like Chevron must tighten the proverbial belt with layoffs, cost cuts, restrictions on share buybacks, etc. That is, prices for oil are weak and getting weaker. So say the big guys who do this stuff for a living.

Ample Supply, Lackluster Demand

Looking back since the pandemic, and tracking broad trends, it’s fair to say that global oil supply has been ample for several years, and that solid levels of supply have contributed to the general price decline of the product.

Plus, it’s also accurate to say that global demand for oil hasn’t grown as robustly as some people might have forecasted. And there’s a profound macro-economic angle to that.

Here at Paradigm Press, we (meaning I and several colleague editors) have discussed on many occasions how the U.S., the West, and many other regions of the world economy are in a global-scale recession.

On occasion, we’ve used the hot-button term “stagflation” to describe the U.S. economy, meaning a mix of inflation and stagnant growth. And again, this was long before Trump reappeared on the Washington power scene in January 2025. If you want to name names, we were talking about the economy of former President Joe Biden and his administration.

Biden’s stagflation has roots in the 2020 economy shutdown of the pandemic, compounded by the spend-spend-spend policies of his administration. That is, from January 2021 and continuing to the last days of his term, Biden’s policies were built around a Niagara of federal spending.

Partly, the Biden spend-a-thon was intended to juice the economy, maintain the fight against the pandemic, and recover from the broad shutdown of 2020 under Trump 1.0. (In other words, we can’t let Trump off the hook for his role in 2020.)

But another angle of the Biden spending machine was a combination of extremist policies, especially his climate-framed politics. This manifested as a Big Government style of industrial policy and planning focused on the so-called “Green New Deal,” aka the Green New Scam.

Along these lines, literally hundreds of billions of Biden-bucks flowed into boondoggle spending programs that not only didn’t grow the economy in any productive direction, but which actually hamstrung true economic progress.

Again, Biden’s legacy to Trump is an economy riddled with a blowout budget that Trump has been unable to alter; plus latent inflation and stagnant growth (aka stagflation), now reflected in those relatively low oil prices.

Low prices don’t imply that we have more and more oil supply out there; and in fact, here in the U.S. output has more or less plateaued. The current issue of concern, which is reflected in falling oil prices, is that we have declining demand for energy due to the stagnant U.S. and global economy.

Bearish Market

In fact, oil’s declining price trend of the past year has recently picked up speed. Oil prices have slipped by more than 15% since the beginning of April. Apparently, this is related to broad-based investor and business worries and concerns about future economic and global growth due to U.S. tariffs.

Plus, to compound the supply situation, markets are absorbing recent news from OPEC+ of production hikes that add up to numbers well over long-established quota limits. The explanation is that many oil producing nations just plain need the money from oil exports – even at lower prices – to pay their national bills.

So now, we have lower demand and slightly higher world supply, which leads to declining oil prices. And this might feel sweet in some respects, but don’t get too comfortable.

That is (and yes, this angle is obvious), many sectors of the economy benefit from lower oil prices. People and businesses everywhere prefer cheaper gasoline and diesel fuel for their cars and trucks. Freight companies, airlines, railways and shipping companies are happy to pay less for fuel.

In other industries, mining companies and agriculture certainly benefit from lower priced fuel, considering how much of the operational budget must go into the fuel tanks of trucks and other heavy equipment. Gold and silver miners, for example, are prime beneficiaries of lower fuel prices, as much of their equipment runs off petroleum.

Chemical companies and downstream users also benefit from lower cost feedstock derived out of petroleum derivatives.

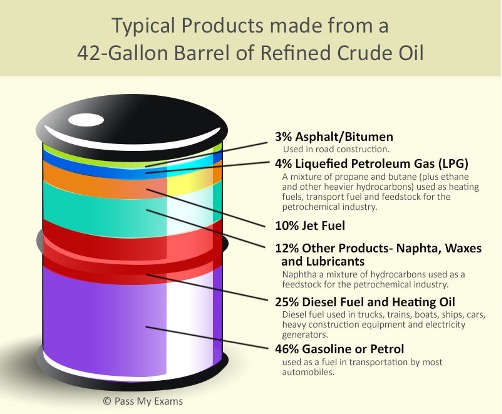

To help understand the myriad of products that come from a barrel of oil, here’s an illustration of what happens to 42 gallons of Brent crude oil from the North Sea:

Products from a barrel of Brent. Courtesy PassMyExams.

It’s all good, right? Well, it’s all good unless it’s the barrel of oil that you had to extract at great effort and cost from, say, the North Sea. Or pick any other oil province on earth, from the Gulf of America to the North Slope of Alaska, and many more locales.

That is, extracting oil is a highly complex and expensive technical process. Wells are expensive to drill, and what’s called “completing” a well is even more expensive, particularly fracking which now supplies over 70% of U.S. domestic oil. What makes it all work is the wellhead price, which pays for all the equipment, articles, labor and services.

At about $57 per barrel, the current price as discussed above, it’s safe to say that most U.S. oil operations are still economic; although many are just barely, sort of, kind of economic. Still, most companies can make a modest profit at that level.

But absolutely, a continuing decline in the price of oil threatens future drilling and overall capital investment in the energy patch.

And this brings us to a certain cognitive dissonance within U.S. energy policy, both under Biden and now Trump. At political levels, the leadership class tends to express a desire for “low prices” at the pump. Indeed, Biden went so far as to drain the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to historic low levels, just to keep the price of gasoline down before midterm elections in 2022.

And now Trump wants to help rebuild American manufacturing based on “cheap” energy to fuel equipment and transportation, plus feedstock materials. Yet low oil prices will doubtless discourage future drilling, and lead to a decline in U.S. oil output. (Of note, for example, oil production in the Texas Permian Basin is now at a plateau; it’s not increasing and will likely soon roll over into decline.)

The point is, politicians can’t have it both ways, not even Donald Trump. He can brag about cheap oil and fuel prices, but the next chapter in this book is a decline in drilling and oil output here in the U.S., not to mention bad economics for international players like Chevron, which I mentioned at the beginning. Again, yes, no wonder that Chevron is laying people off.

And this brings us to the final point of this note, namely how can you play it? Well, be sure to keep an eye out for upcoming issues of the Jim Rickards Strategic Intelligence franchise, because I’ll have much more to say about oil drilling, fracking, oil service companies, and investment themes that have high payoff potential in these uncertain times.

Yes, I’ll leave you hanging on this for details. But I promise… In future reports I’ll tell you tales to astonish, all about opportunities in the oilfields. And yes, you can make money out of all this.

With that, I’ll end here and thank you for subscribing and reading.