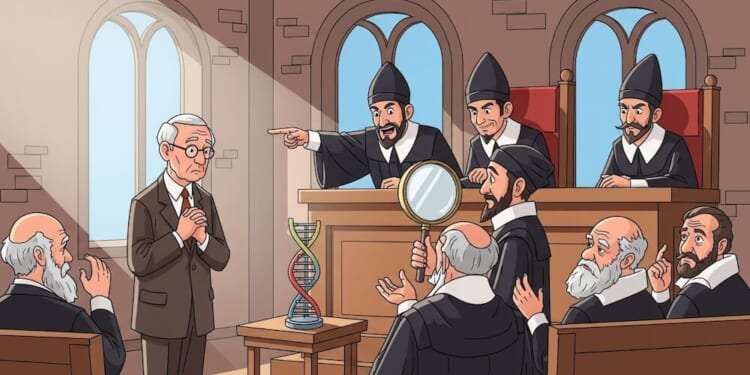

In the grand pantheon of science mythos, Galileo is the poster child for “the scientist forced to recant by the powers that be.” And boy, have TPTB regretted it ever since!

But they didn’t at the time.

The modern analogue isn’t an astronomer with a telescope, but a molecular biologist with a model kit. That man, James D. Watson, is someone who cracked one of the great codes of biology (the structure of DNA) and then became a figure whose legacy is tangled in science, society, and politics because he wouldn’t back off from the science of controversial outcomes.

When scientific findings or claims collide with the prevailing social or political consensus, how does the system respond? And what does that tell us about the integrity of science, the tyranny of scientism, and the freedom to ask the hard questions? The societal and political reactions to such collisions often needlessly hinder scientific progress.

With the advent of Artificial Intelligence, those questions will only become more important to answer.

The Discovery: Watson, the Genius

Watson, together with Francis Crick and drawing on Rosalind Franklin’s X-ray work, announced in 1953 that DNA forms a double helix — a revelation that transformed genetics and medicine. He won the Nobel Prize in 1962. For decades, he occupied the pinnacle of the molecular biology revolution, advancing healing, engineering, and understanding of life. In this sense, his credentials as “giant of science” were unchallenged — until the broader questions began to emerge.

Galileo Redux: Watson and the “E pur si muove” Moment

It is with his later views that the Galileo analogy begins to tighten. One commentator wrote:

“In effect, Watson was saying what Galileo is supposed to have remarked under his breath when forced by the Church to recant his belief… ‘E pur si muove. And yet it moves.’”

Let’s unpack the comparison. Galileo challenged the dominant cosmology (Earth at the centre of the solar system) and faced the full weight of ecclesiastical power.

Watson, decades later, advanced ideas (or at least flirted with claims) that challenged prevailing social-scientific taboos (race, intelligence, environment vs heredity). For some, this earned him the “modern-day Galileo” label.

But—and this is crucial—the analogy breaks down in meaningful ways. Galileo’s empirical observations (e.g., the moons of Jupiter) challenged a cosmic consensus; Watson’s controversial comments pertained to heredity, race, and IQ—areas deeply entwined with history, ideology, and social policy.

And Galileo’s work was suppressed by authorities who feared theological upheaval. Watson’s suppression (or ostracism) came from scientific institutions and the court of public opinion. The venue may have changed, but the witch trial is still the same. A scientist says something politically unpalatable, then the system reflexively responds.

When Science Meets Political Consensus

In the view of many, Watson crossed a line when he publicly speculated that average intelligence may differ across populations, and that genetic factors may underlie those differences. For example, in 2007, he told the Sunday Timeshe was “inherently gloomy about the prospect of Africa because all our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours—whereas all the testing says, not really.”

His employer, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), responded by revoking his honorary titles:

“Dr Watson’s statements are reprehensible, unsupported by science … the laboratory condemns the misuse of science to justify prejudice.”

The mainstream of science (and the broader academic-cultural milieu) had come to see race-intelligence hypotheses as not only scientifically dubious but socially toxic. Watson’s comments ran head-on into that.

Science organisations are sensitive to reputational damage (and the subsequent loss of funding). When Watson’s remarks became public, CSHL acted to distance itself.

Hereditarian views about intelligence and race inevitably trundle into politics. The clash is with science and, perhaps even more so, with social beliefs about equality, opportunity, and identity.

The mob framed Watson’s statements not merely as scientific speculation but as moral judgments. That intensified the response.

The Galileo parallel: A claim that challenges a deeply held consensus (cosmic or social) invariably meets resistance. The instrument of resistance may change (from the Inquisition to institutional cancel culture), but the pattern remains the same.

The Irony, Caution, and Woke Gauntlet

Here’s the rub: Watson was one of the greatest scientific minds of his generation. His DNA work changed the world. Yet his later legacy became entangled and undone by what many consider ill-advised public statements. That raises two interlocking problems:

If a brilliant scientist can be ostracised for stepping outside accepted bounds, does that chill legitimate inquiry? Does the fear of “getting it wrong” or “sounding controversial” stifle the next big insight?

Watson’s controversial statements were not just pure empirical claims—they blended speculation, interpretation, and judgment. A scientist can be punished not just for being wrong, but for being perceived to be morally or socially problematic.

In that sense, Watson is a cautionary tale for scientists and for society. The dominant social lens of the moment can become an inadvertent orthodoxy. When you challenge it—even as a legitimate scientist—you may get hammered. And if you’re celebrated for earlier work, your fall can be spectacular.

Why This Matters

It self-evidently matters. However, sometimes we need to reiterate the reasons why conflicts like this occur.

First, the interplay between innovation and consensus is a delicate one that requires careful navigation. Just like markets penalize dissent when the herd is wrong (and reward it when the herd is right), science, too, can penalize dissenters, even if they may be correct.

Next, the government-mandated private sector shutdown during 2020-2022 threw into sharp relief he risk of groupthink in science. If saying the “wrong” thing gets you cancelled, the incentive is to conform. That suppresses transformative questions.

Third, Watson’s comments triggered outrage in part because they blurred the line between data and ideology. Readers should ask: Who defines what is “acceptable” science? What gets labelled “fringe”?

Finally, nuance matters. Watson’s life is neither pure heroics nor pure villainy. He made monumental contributions — and he later made statements many scientists reject. His legacy, though immense, is now deemed “complex.”

Wrap Up

Just as Galileo refused to recant, muttering “and yet it moves,” Watson—perhaps differently—asserted provocative hypotheses and endured the institutional consequences. Whether you think Watson was right, wrong, or somewhere in between, the chilling effect on scientific inquiry is real.

It’s sad to see a man who gave so much receive so little in return now that he is gone.

Here’s some food for thought:

Is the mob too quick to cancel scientists when their public comments offend the social consensus?

Does the structure of science today protect breakthrough ideas — or only “safe” ideas?

When it comes to controversial hypotheses (e.g., on intelligence, genetics, risk), does the marketplace of ideas in science operate freely, or is it rigged?

Hopefully, we’ll get the answers right one day.