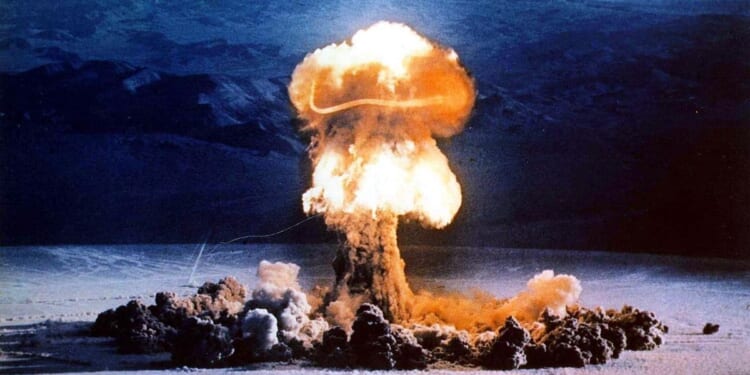

President Trump’s threat to resume nuclear weapons tests has sparked unease in Moscow and Beijing and triggered frustration among some U.S. nonproliferation experts who say the administration is sending mixed signals on an intensely sensitive global security issue.

The president announced Oct. 29 that ending Washington’s more than three-decade moratorium on tests is warranted because Russian and Chinese nuclear stockpiles are approaching U.S. levels and because other nations are already involved in some degree of testing.

The comments underscored growing uncertainty about the future of global nonproliferation standards. They also raised the question of whether the world is heading into a new era of great power nuclear detonation tests.

Former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said that if Mr. Trump is justified in airing his options, then he may be creating a setting for a major policy shift.

“The principle must be: We need to do everything necessary to convince our adversaries that we know our stuff will work,” Mr. Pompeo told The Washington Times in an interview. “That would include testing of the weapons themselves, if that’s what’s required.”

A Truth Social trigger

Mr. Trump wrote on his Truth Social platform that “Because of other [countries’] testing programs,” he would have “the Department of War to start testing our Nuclear Weapons on an equal basis.” Days later, in an interview with CBS’s “60 Minutes,” he said the U.S. is “the only country that doesn’t test” its nuclear weapons.

The comments triggered swift backlash. Beijing sharply denied that it had carried out any nuclear tests in recent years. Russian President Vladimir Putin responded by signaling that his government would actively consider testing. Officials in Moscow said they were seeking more information about what the U.S. policy shift on testing would entail.

The developments have also drawn eye-opening reactions from U.S. nonproliferation experts, including Daryl Kimball, executive director of the nongovernmental Arms Control Association. He said he and his colleagues also wanted more information.

“The Russians say they want to talk. The Chinese say they want to talk,” Mr. Kimball told The Times. “What does [Mr. Trump] want out of the Chinese or the Russians, if he’s threatening nuclear testing as his big threat?”

Russian presidential press secretary Dmitry Peskov said the issue of nuclear testing is “too serious a substance” to leave any room for interpretation. “We really need clarification of what exactly was meant,” Mr. Peskov said in a Russian state media interview published Sunday.

Mr. Putin has directed his top security advisers to begin assessing how to restart Russia’s nuclear testing programs. Top-ranking Russian generals have said they are ready to resume the programs.

Mr. Pompeo told The Times that the situation represents a direct test of the deterrence model that has been in place since the Cold War. In many ways, the model is defined by a delicate dance between great powers around what cards to play publicly and privately to maintain peace.

“The central premise of deterrence is that our adversaries know that our stuff will actually work and that they know we’re confident that it will,” said Mr. Pompeo, who served as CIA director and then as secretary of state in Mr. Trump’s first term.

Critical nuclear explosive testing by Russia, China or the United States would violate the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, which the countries signed in 1996. The treaty has been signed by 187 countries, though three — India, Pakistan and North Korea — have never fully ratified it. North Korea is the only country to conduct widely known nuclear detonation tests since, most recently in 2017.

Russia claims it has conducted only noncritical nuclear testing over the years.

During the days leading up to Mr. Trump’s Oct. 29 Truth Social posting, Russian officials revealed that they had recently conducted tests of different nuclear weapon delivery vehicles: the Burevestnik RS-SSC-X-09, a nuclear-powered and nuclear-capable intercontinental cruise missile known as Skyfall, as well as the Poseidon, a large nuclear-powered and nuclear-capable uncrewed underwater vehicle.

The United States also has carried out delivery system tests, including of the nuclear-capable Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missile.

Energy Secretary Chris Wright said in an interview with Fox News last week that any U.S. tests would not violate nonproliferation treaties that Washington has signed. “I think the tests we’re talking about right now are systems tests,” he said. “These are not nuclear explosions. These are what we call noncritical explosions.”

Clarity needed

Mr. Kimball told The Times that the types of tests the Trump administration may be considering carry uncertainties.

He said the White House should further clarify to other countries what Mr. Trump meant by asserting that the United States will resume testing “on an equal basis.”

“It’s a very convoluted statement,” said Mr. Kimball, noting that the Department of Energy, not the Department of Defense that Mr. Trump referenced in his post, maintains the U.S. arsenal of nuclear warheads and is responsible for any nuclear explosive testing.

“I’ve worked on the subject for 35 years. No other country, except for North Korea, has conducted nuclear explosive tests in this century,” Mr. Kimball said.

U.S. intelligence assessments appear to suggest otherwise.

Last week, Sen. Tom Cotton, Arkansas Republican and chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, said CIA Director John Ratcliffe had confirmed to him directly that U.S. intelligence had indications of “super-critical nuclear weapons tests in excess of the U.S. zero-yield standard.”

Questions have been raised about whether any of the three — the U.S., Russia or China — has carried out low-yield nuclear bomb tests in a classified setting. Each claims publicly to have adhered to the no-test standards of the existing nonproliferation regime.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning said last week that China has not conducted any such nuclear bomb testing in recent years.

“China is committed to peaceful development, follows a policy of ‘no first use’ of nuclear weapons and a nuclear strategy that focuses on self-defense, and adheres to its nuclear testing moratorium,” Ms. Mao said. “We stand ready to work with all parties to jointly uphold the authority of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty.”

Russia also has denied conducting any critical explosive tests. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said Tuesday that the country will resume nuclear weapons tests only in response to other nuclear-powered nations.

The future of nonproliferation

During Mr. Pompeo’s tenure as secretary of state, the U.S. left the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. An argument similar to one used in concert with NATO to end the 1987 treaty, signed by President Reagan, is playing out.

The first Trump administration said Russia consistently violated the treaty, making it a useless agreement that only weakened the United States.

Another nonproliferation agreement at issue is that of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty.

The current version of the agreement, the New START Treaty, is set to expire in early February. The treaty, signed by President Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev, limits each country to no more than 1,550 deployed nuclear warheads and 700 deployed missiles and bombers.

Mr. Trump’s recent comments have spurred speculation that he is intentionally instigating conversation around nuclear testing and stockpiles ahead of renegotiations of New START.

“I hope so,” Mr. Pompeo said when asked about the speculation. He said that although a treaty with Russia is good, even if Moscow acts as an unreliable partner on testing and standards, the need to include China in any future version of START, with its growing arsenal, is critical.

“The world in which those treaties were originally designed was a world where there were really only two global competitors that had weapons programs at scale,” Mr. Pompeo said. “There are now three.”

China’s stockpile of nuclear weapons is growing rapidly, U.S. intelligence reports say. Although the U.S. retains its lead in the number of weapons, Mr. Trump said, China is expected to close that gap within five years.

In September, Mr. Putin called the New START the “last major political and diplomatic achievement in the field of strategic stability.” He offered to extend the bilateral agreement for an additional year beyond its February expiration date.

Mr. Putin directed his government at the time to “maintain close oversight” of U.S. activity around strategic defense, including missile defense and space-based interceptors.

Also in September, Geng Shuang, Chinese ambassador to the United Nations, said Beijing remains supportive of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty and stressed that “the nuclear weapon states should all honor their moratorium commitments on nuclear testing, effectively reduce the role of nuclear weapons in national security policies, and make clear commitments to no first use of nuclear weapons.”

Mr. Trump mentioned numerous times during his campaign for president that nuclear weapons were “too powerful.” During an interview podcast with comedian Andrew Schulz in 2024, Mr. Trump said his first-term administration was “close to a deal for getting rid of nuclear weapons.”

“It would be so good for all countries,” Mr. Trump said.

It remains to be seen where his more recent pledge to ramp up testing will lead.

Mr. Pompeo hopes it drives results toward deterrence, not distrust.

“If we’re going to have strategic arms conversations, we need those that are in possession of large quantities of strategic arms to participate,” the former secretary of state said. “Let’s get the relevant parties that can affect strategic deterrence to the table and either all agree that we’re going to limit ourselves or go on about our business.”