ISTANBUL — Iran’s rejection of Turkey as a venue for nuclear talks with the United States this week exposed a hard truth about Middle East diplomacy: No one in the region is expecting a breakthrough.

What Gulf states want is time.

Tehran insisted negotiations be moved from Istanbul to Oman and restricted to uranium enrichment alone. Turkey had offered to host broader regional discussions. The dispute was resolved Wednesday, when both sides confirmed that talks would begin Friday in Muscat, Oman’s capital — but only after a quiet diplomatic push by Arab and Gulf leaders urging Washington not to walk away.

Multiple Arab and Muslim governments pressed the Trump administration to accept Iran’s request, warning that canceling the talks could accelerate escalation and destabilize already fragile Gulf security, according to U.S. and regional officials cited by Reuters, Axios and Gulf media.

Protesters burn pictures of Iranian Supreme …

more >

Interviews with diplomats and analysts across three Gulf capitals suggest regional powers are not betting on a resolution. They are trying to prevent miscalculation long enough for containment strategies to hold.

“From a strict risk-analysis perspective, these talks are viewed as volatility management rather than risk reduction,” said Mostafa Ahmed, a researcher at Al Habtoor Research in Dubai who specializes in Gulf security frameworks. “True risk reduction would require a structural settlement of the core adversarial issues, which remains distant.”

That distinction helps explain why Iran rejected Turkey’s offer and insisted on Oman’s established back channel — and why Gulf Arab states moved quickly to preserve the talks even as Washington and Tehran remain sharply divided over their scope.

Friday’s talks are scheduled to begin at 10 a.m. in Muscat, Iran’s Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi confirmed Wednesday, thanking “our Omani brothers for making all necessary arrangements.”

The negotiations mark a return to the quiet coastal capital nestled against the Hajar Mountains where secret Obama-era talks laid the groundwork for the 2015 nuclear deal. Iranian and U.S. delegations held multiple rounds there last year before fighting in the region halted the process.

Unlike Qatar’s high-profile Taliban talks or Saudi Arabia’s heavily publicized hosting of Russia-U.S. diplomacy, Oman typically conducts negotiations behind closed doors. But these talks are unusually visible — and unusually fragile.

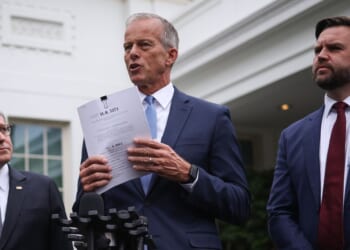

They will be indirect, with Oman serving as mediator. Mr. Araghchi will lead the Iranian delegation. White House special envoy Steve Witkoff represents the United States.

The venue change came after days of uncertainty over whether the meeting would happen at all. U.S. officials confirmed that preparations resumed only after sustained lobbying by regional leaders warning that a collapse would sharply raise the risk of military escalation.

Turkey’s triangulation

Turkey initially positioned itself as a logical venue. Ankara maintains diplomatic relations with both Washington and Tehran, and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has consistently urged de-escalation over military confrontation.

Mr. Erdogan confirmed Thursday that Turkey had been actively working to prevent tensions from tipping into open conflict, even as disagreements persisted over expanding the talks beyond the nuclear file.

“Turkey is doing its best to prevent escalation,” he said.

Iran, however, had other priorities — and the talks briefly teetered on collapse as disputes over venue and scope intensified earlier this week.

Tehran wanted negotiations limited strictly to the nuclear file and conducted through Oman’s discreet bilateral channel — the same mechanism that facilitated early discussions leading to the 2015 deal.

“Iran insisted on Oman because of trust,” said Mahdi Ghuloom, a Dubai-based researcher at the Observer Research Foundation Middle East. “Oman has built long-term trust with Iran. This is the moment for Oman to prove the value of that trust.”

Serhan Afacan, head of the Center for Iranian Studies in Ankara, said Turkish officials are not treating the venue shift as a setback.

“Turkey is not very concerned about the venue of negotiations,” Mr. Afacan said. “Istanbul would have been an option, but Ankara does not insist that it must be Istanbul.”

What Turkey does care about is avoiding escalation — and not owning a diplomatic process that could collapse under U.S. and Iranian red lines.

“People here take the risk of military escalation extremely seriously,” he said. “Turkey is more comfortable stepping back than being tied to a process it cannot control.”

The decision to keep the talks alive did not come from Washington or Tehran alone.

Qatari Prime Minister Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman spoke with Mr. Araghchi this week about “efforts to reduce tension,” according to Iran’s IRNA news agency. He also consulted with Saudi Defense Minister Prince Khalid bin Salman in Doha.

Kuwait’s prime minister urged “common sense” to prevail. United Arab Emirates diplomatic adviser Anwar Gargash warned publicly that the region “does not need another confrontation.”

A White House official told The National that planning resumed only after lobbying by several Arab and Muslim leaders. Axios reported that at least nine regional governments passed messages to senior Trump administration officials urging them not to cancel the meeting.

Behind the pressure lies a shared fear: regime instability in Iran could spill outward — or a cornered Tehran could lash out at U.S. bases hosted on Gulf soil.

Crude calculations

Oil markets reacted immediately to confirmation of the talks, with crude prices sliding more than 1% as fears of near-term disruption in the Strait of Hormuz briefly eased — a signal Gulf capitals quietly monitor as a proxy for escalation risk.

Oman’s role stems from decades of what Gulf analysts describe as “aggressive neutrality.” Unlike other Gulf states, Muscat maintained diplomatic relations with Iran even during acute regional crises.

“Oman is seen as disinterested — not acting out of self-interest or currying favor with Washington,” Mr. Ghuloom said. “It is not viewed as a likely target, which makes it uniquely credible.”

Mr. Ahmed noted that institutional capacity matters.

“Oman’s bureaucracy is more professional and disciplined than ever,” he said. “That institutional maturity is part of why Oman can play this role now.”

For Iran, Oman offers something Turkey cannot: a proven mechanism for keeping talks narrow, bilateral and shielded from public pressure.

When talks briefly shifted to Rome last year, Iranian officials complained about excessive media presence. Tehran also worries about exiled opposition groups mobilizing protests outside European venues.

Tehran wants negotiations focused exclusively on its nuclear program — not ballistic missiles, regional proxies or domestic repression. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has said all those issues must be addressed. That disagreement remains unresolved.

Gulf Arab states are approaching the talks with expectations that may confuse Washington.

“Washington tends to see diplomacy through a binary lens — a deal or a failure,” Mr. Ahmed said. “The Gulf sees the process itself as infrastructure.”

Success is not defined by a signing ceremony but by sustained contact.

“If the talks merely create a reliable channel that prevents accidental war, that is success,” he said. “The Gulf measures efficacy by preventing deterioration.”

Turkish officials express a similar view, privately cautioning that the danger lies not in slow diplomacy, but in a sudden collapse that leaves military options as the only remaining path.

Mr. Ghuloom agreed. “The biggest fear is collapse before the first round is even completed,” he said.

The memory of January’s near-miss looms large. Talks were previously scheduled — then overtaken by military escalation.

“Last time talks were planned, war broke out,” Mr. Ghuloom said.

Nuclear first, everything else later

Turkish and Gulf perspectives align on one key point: sequencing over bundling.

Rather than demanding comprehensive negotiations covering nuclear, missile, proxy and human-rights issues simultaneously, regional analysts favor addressing the nuclear file first.

Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan recently told Al Jazeera his advice to Washington would be to “close the nuclear file first, then move on to other issues,” Mr. Afacan said. “The United States should not be greedy at the negotiating table.”

Mr. Ahmed acknowledged the risk.

“Sequencing gives Iran economic breathing room while postponing regional issues,” he said. “But Gulf states accept that risk because they do not expect the Oman talks to solve proxy conflicts anyway.”

Instead, they are pairing diplomacy with independent security hardening and deeper bilateral defense ties with Washington and Europe.

If Iran wants Gulf states to believe these talks represent genuine de-escalation rather than tactical delay, Mr. Ahmed said, Tehran must demonstrate restraint in observable ways.

First is maritime behavior. Any “seizure of commercial vessels, or even aggressive painting of tankers by IRGC swift boats, immediately invalidates diplomatic messaging,” he said.

That concern is not hypothetical.

This week, U.S. Central Command reported that Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps approached a U.S.-flagged tanker at high speed in the Strait of Hormuz and threatened to board and seize it. The U.S. military also shot down an Iranian drone that “aggressively” approached the USS Abraham Lincoln aircraft carrier in the Arabian Sea.

Second is infrastructure sanctity. Mr. Ahmed called this “the absolute red line” — no kinetic attacks on energy or desalination facilities. “Restraint here is the baseline requirement for the ‘decompression’ thesis to hold.”

Third is proxy discipline. Rather than demanding Iran abandon its proxy networks entirely, Gulf states are watching targeting choices.

“A demonstrable shift away from targeting GCC sovereign territory or waterways is the key signal of intent they are looking for,” Mr. Ahmed said.

For Bahrain, which hosts the U.S. Fifth Fleet and faces Iran-backed opposition groups, the stakes are particularly acute.

“Any strike could affect civilians,” Mr. Ghuloom warned. “There are allegations about Iranian-backed activity, and the fear is that escalation could reach a point where Iran directs missiles toward Gulf countries.”

Eyes on Israel

Complicating regional coordination is disagreement over which actor poses the greater threat: an unstable Iran or an aggressive Israel.

For Turkey, the answer is clear.

“Israel is currently perceived as a more immediate threat — particularly because of Israeli policies in Gaza, Syria, and elsewhere,” Mr. Afacan said.

Other Gulf states, particularly those that normalized relations with Israel through the Abraham Accords, see Iran’s nuclear program, missiles and proxies as existential challenges. The UAE and Bahrain, which established ties with Israel in 2020, maintain this calculation despite periodic tensions.

“None of the countries in the region want Iran to possess nuclear weapons,” Mr. Afacan said. “However, for countries like Turkey, Israel is currently perceived as a more immediate threat.”

From Israel’s perspective, Mr. Ghuloom said, the Trump administration may have ended last June’s war too early.

“There’s a sense that Israel’s military objectives in Iran haven’t been completed — and political objectives even less so,” he said. Proposals such as installing the former Shah’s son have attracted support in Israel but remain remote.

Mr. Ahmed described this split as dividing Gulf states into a “defensive deterrence” camp and a “diplomatic insulation” camp. The first prioritizes security architecture. The second prioritizes de-escalation.

Oman sits at the intersection — facilitating diplomatic insulation while the deterrence camp quietly supports it as a safety valve.

As U.S. and Iranian negotiators prepare to meet in Muscat, Gulf states are planning for what Mr. Ahmed calls “managed stagnation” — talks without breakthrough, but without war.

“The process becomes a container for tensions,” he said. “Low-level friction continues, but high-intensity conflict is avoided.”

The alternative is “compartmentalized breakdown” — negotiations collapse, tensions spike, but escalation remains geographically limited.

What no one appears to be planning for is a comprehensive resolution. The structural drivers of U.S.-Iran competition — nuclear ambitions, regional proxy networks, ideological opposition — remain unchanged.

President Trump has deployed carrier strike groups to the Persian Gulf. Iran’s supreme leader has warned against foreign intervention.

Mr. Ghuloom captured what regional powers are actually hoping for from Friday’s talks.

“Success is simply getting past the first round without collapse,” he said.