First came the tolling of bells: the First Church of Boston, then the Second Church, then smaller ones joining in, the sound rolling through Boston like a summons. The streets cleared quickly, barefoot boys darting to claim the best vantage points. It was summer, and the air stank of old straw laid down to soak up urine and horse droppings, mixed with the sharp tang of fresh fish hauled in from the harbor that morning. Inside inns and taverns, conversations fell away as people shifted toward windows mysteriously clean for the first time in weeks.

British officers and soldiers quieted. Something was happening, and they didn’t think they’d like it.

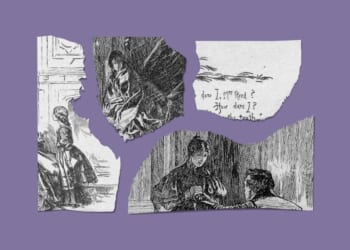

The mourners came first, riding black-plumed horses slowly down the sloping streets, three abreast, filling the narrow lane. The riders were dressed entirely in black, holding torches aloft despite the bright afternoon sun. Children ran ahead and alongside the procession, handing out black ribbons to anyone still standing in the street, darting inside to hand them to tavern patrons. Many tied them on arms or wrists, grinning. They were already in on the joke.

Now came the star of the show. Behind the mourners came a coffin, draped in black cloth and borne by six men, also dressed in black. On one side was painted Liberty. On the other, Freedom.

A man in a wide-brimmed hat walked before it with a proclamation, calling out solemnly: “Oyez, oyez. All bow their heads and mourn the death of that which we hold most precious, sacred Liberty, mercilessly slain by the King’s men on this day of our Lord.”

Redcoats scowled. Colonials howled. The point being made by the infamous Sons of Liberty was very clear.

What That Scene Actually Was: Prank Politics

It is tempting, especially from a modern distance, to read the mock funeral for Liberty as protest. But what unfolded in Boston that day belonged to an older political tradition: prank politics, the use of ritualized mockery to undermine authority by stripping it of seriousness.

The bells, the coffin, the solemn procession all borrowed the language of civic ritual and turned it back on power. The humor lay in the precision, not the chaos. Instead of arguing policy or demanding concessions, the procession posed a quieter and disruptive question: why should this authority be taken seriously at all?

Mockery works on legitimacy, not force. It circulates publicly, invites both active (creator) and passive (audience) participation, and tests power for its ability to absorb laughter without cracking. When authority responds with fear or repression, the joke has made the point, and authority looks like the bully. Prank politics slows escalation, preserves space for correction, and often appears just before more dangerous forms of conflict take hold. It is, in a way, the last chance to deescalate before the fight.

Prank Politics Today

Today, conservative prank politics travels electronically: memes, short videos, surprise journalism, and the gleeful inversion of progressive protest tactics. Sometimes it’s as simple as turning a movement back on itself, as Blue Lives Matter did when activists were misdirected away from their intended target and toward their own leadership or worse. The aim isn’t harm or even cruelty. It’s exposure. Humor replaces outrage; laughter drowns out protest. Ridicule steps in only after argument has been rejected outright.

Amelia began as mockery, hijacking a character designed to channel youthful doubt into unquestioning obedience. It didn’t stay a joke. It grew into an ecosystem, a shared banner that young people could rally around without instruction. The same thing happened with memes aimed at JD Vance. What started as an attempt at shaming collapsed when Vance embraced the joke, reposted it, and let others run with it. The mockery flipped, then multiplied, becoming a way to share love for Vance rather than mock him.

None of this explained itself. It trusted the audience. Like the Sons of Liberty at the beginning, today’s prank politics relies on confidence over grievance, legal restraint over outright provocation. And like the Sons of Liberty, it has emerged in response to authority that has become moralized, insulated, and unable to laugh at itself.

Back to the Sons of Liberty: The Original Template

Seen clearly, the Sons of Liberty look less like proto-radicals and more like the early practitioners of a durable political technique.

They began with mockery because mockery works, not as insult, and not as sermon, but as social glue. Mock funerals, hanged effigies, dressing up as Indians to turn Boston Harbor into the world’s largest cup of tea, these were jokes in the deepest sense. They invited recognition. They assumed shared norms. They pulled people together by letting everyone see the same absurdity at once.

That is what modern critics often miss. Humor is not primarily a weapon against enemies. It is a way of binding insiders. The Sons of Liberty did not explain their jokes or moralize them. They trusted their neighbors to understand. Participation mattered more than persuasion. Laughter mattered more than outrage.

Once people could laugh together at authority, they no longer feared it in the same way. Legitimacy drained quietly, without manifestos or lectures. Only later — after mockery had done its work — did escalation become thinkable. The prank came first. The war came last.

What the Sons of Liberty practiced did not arise in isolation. It drew on an older Anglo tradition in which humor functioned as civic correction rather than rebellion. In England, satire long disciplined power without seeking to overthrow it. Jonathan Swift savaged the British government’s treatment of the Irish. Pamphlets, cartoons, caricature, and public ridicule applied pressure socially instead of militarily. Authority was expected to endure mockery as proof of legitimacy. When it could not, everyone noticed.

That sensibility crossed the Atlantic intact. Colonial Americans inherited not just English law, but English irreverence. Across the Anglosphere, ridicule aimed upward signaled engagement, not sedition. Humor kept dissent communal rather than conspiratorial. Modern prank politics draws on that same inheritance. It is not inventing something new. It is reactivating a cultural memory in which laughter binds communities, disciplines excess, and corrects authority without immediately seeking its destruction.

The power of prank politics does not come from transgression, but from restraint enforced informally and collectively. Boundaries are maintained through reputation rather than punishment. Participants know when a joke clarifies and when it merely provokes. When mockery turns cruel or incoherent, it doesn’t need to be banned; people stop spreading it. No one laughs, and the joke dies. This internal discipline is easy to miss from the outside, where the absence of centralized control is mistaken for chaos. In reality, informal norms are often stricter than formal rules, because they operate through belonging. Humor persists only as long as it binds rather than fractures, and that collective discernment is what keeps ridicule corrective instead of destructive. It is, ultimately, populist in the purest sense.

The French Revolution: When Humor Disappears

The French Revolution offers a sharp counterexample, not because it lacked dissent, but because it lacked humor. Where Anglo political culture relied on ridicule to discipline power, revolutionary France treated mockery as a threat to be eliminated.

As the revolution intensified, politics became sacred. Ideology replaced custom. Moral seriousness crowded out irony. Satire became suspect. Laughter no longer signaled engagement; it signaled disloyalty. Jokes were recoded as crimes, and ridicule as treason.

Without humor, informal regulation collapsed. There was no shared laughter to mark excess, no communal pressure to slow escalation. When those governing took themselves too seriously, horror followed, just as it did with Marxism and communism. Correction gave way to purification. Every failure demanded moral explanation. Every disagreement required denunciation. Violence followed not as an aberration, but as the only remaining instrument once mockery had been outlawed.

“That’s Not Funny!”

That failure mode has not remained in the eighteenth century. It reappears whenever politics becomes moralized to the point that humor is treated as contamination rather than correction.

In contemporary Britain, this instinct has been taking legal form. Comedians and ordinary citizens are questioned, fined, or arrested and even imprisoned over jokes and “mean tweets,” not because they incite violence, but because they violate enforced moral sensibilities. Humor is reclassified as harm. Mockery is taken seriously, becoming evidence rather than a healthy corrective. The law is pressed into service to protect seriousness itself.

In the United States, the pattern is cultural rather than statutory, but no less visible. American progressivism, perhaps inheriting the attitude from famously humorless feminism, reacts to conservative humor with genuine horror. Jokes are framed as aggression and laughter as cruelty. Worse, what passes for progressive “humor” increasingly resembles political commentary with a punchline stapled on. It is didactic, joyless, and tightly policed. It signals membership. It does not bind.

Laughter Before Fire

Laughter is often called medicinal, but the truth is, it creates and holds together a healthy society. Humor diffuses fear, slows escalation, and preserves a shared civic space even when disagreement is sharp. Laughter allows people to register gentle disapproval without immediately sorting themselves into enemies. It corrects without demanding rupture.

Mockery also removes judgment from the hands of the powerful. Prank politics wrenches legitimacy away from courts, experts, and supposed moral authorities, placing power back in the hands of the public. The audience decides what lands, what spreads, and what dies. Prank politics appears before revolutions and disappears during them. It does not reject order, but rather determines whether order can be corrected without extreme measures. Where laughter circulates, reform remains possible. Where it does not, pressure accumulates until something breaks.

The American Revolution did not begin with gunfire. It began with fake coffins, men dressed up as Indians, satirical cartoons, mocking broadsheets, and laughter carried through narrow streets. Before authority was resisted, it was mocked. Before it was fought, it was tested for its ability to endure ridicule.

That pattern has never disappeared. It reemerges whenever power grows moralized, insulated, and humorless. Prank politics is not a rejection of order, but an early-warning system. It signals that legitimacy is thinning and that correction is still possible if laughter is allowed to do its work.

The Sons of Liberty understood this instinctively. So do modern pranksters and memers and all-around clever people with an agenda. They rely on confidence rather than grievance, shared recognition rather than coercion, humor rather than fear. They trust their audience. They laugh first.

In the best circumstances, they also laugh last.

Editor’s Note: PJ Media is here to make our culture great again, rather than fearful and false. Join PJ Media VIP and use the promo code FIGHT to get 60% off your VIP membership!