Tuesday, Jan. 28, 1986, dawned clear and very cold at Cape Canaveral, Fla. The temperature was 28 degrees on the launch pad where the space shuttle Challenger was expected to finally take off.

The mission had been delayed five times in the last week due to weather, technical glitches, and delays relating to other shuttle missions. Because of the payload the ship was carrying, there was a narrow launch “window” that would allow the shuttle to achieve precisely the right orbit to deploy its satellite payload.

The constant delays put enormous pressure on NASA managers. The launch was timed so Christa McAuliffe, the first civilian in space, could deliver lessons from space to school children. President Ronald Reagan was also scheduled to give his State of the Union address that evening, and NASA officials reportedly wanted to give him a successful launch to mention in his speech.

This pressure to finally get off the pad is part of why managers overruled the engineers who warned that the freezing temperatures on January 28 were dangerous for the rocket’s O-rings.

These rings connected the three sections of the solid rocket boosters (SRBs). They were supposed to expand at ignition and form an air-tight seal to prevent the scorching gases from escaping.

NASA had been lucky to avoid catastrophe on previous missions, as the previous launch videos clearly demonstrated. At least half of the 24 successful shuttle missions had O-ring problems: the seals failed, and there were partial burn-throughs of the rings.

But NASA went ahead anyway, calling the O-Ring problem an “acceptable risk.” On Jan. 28, 1986, the extreme cold at launch (36°F) was so far outside the “experience base” of those previous 14 missions that the safety margin finally vanished.

That day was 15 degrees colder than any previous Space Shuttle launch. The freezing conditions caused the rubber O-rings in the rocket boosters to stiffen, preventing them from sealing properly and leading to the structural failure.

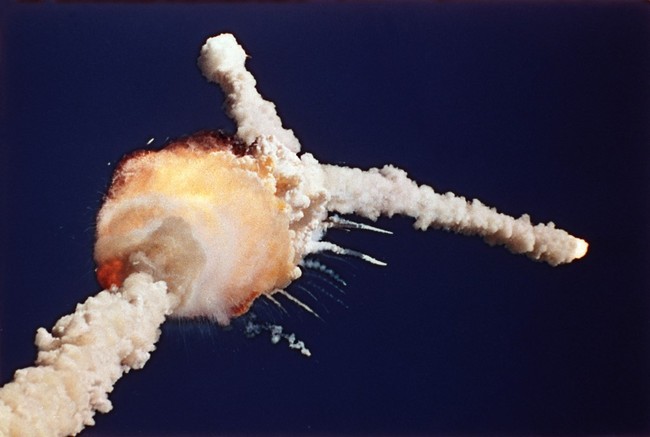

Within seconds of launch, the O-ring melted away, and a stream of white-hot burning fuel began to eat away at the skin of Challenger’s liquid fuel rocket. Just 73 seconds after launch, the liquid fuel of the booster ignited, blowing up the shuttle and its seven crew members.

USA Today took a look at the seven crew members selected for the doomed Challenger mission:

- Francis R. Scobee, the mission commander from Cle Elum, Wash., and an Air Force test pilot

- Michael J. Smith, the pilot from Beaufort, N.C., and a commander in the Navy

- Judith A. Resnik, a mission specialist from Akron, Ohio, who in 1978 was among the first astronaut class containing women

- Ellison S. Onizuka, a mission specialist from Hawaii who was on active duty with the Air Force until he was selected as a NASA astronaut in 1978

- Ronald E. McNair, a mission specialist from Lake City, S.C., with a doctorate in physics and a black belt in karate, who became one of the first three black Americans selected as a NASA astronaut

- Gregory B. Jarvis, a payload specialist from Detroit, who was not a NASA astronaut, but his company made him available for this mission

- S. Christa McAuliffe, a non-astronaut civilian from Boston, was selected from among more than 11,000 applicants to become the first teacher in space.

Red flags were being raised across the U.S. space community before the launch. Specifically, MortonThiokol, the manufacturer of the liquid fuel booster, was adamant about not launching unless the temperature at the launch site was 53 degrees. It was 38 at the time that Challenger lifted off, and several Morton engineers were shaken that their specific warnings weren’t heeded. They felt that NASA put undue pressure on Morton executives to launch.

Several lower-level NASA managers listened to what Morton was saying about the launch temperature but inexplicably failed to pass the warning on to their superiors.

The Rogers Commission, the presidential body formed to investigate the Challenger disaster, concluded that NASA’s decision-making process was “flawed” and that the agency was under “relentless pressure” to maintain an unrealistic launch schedule.

Space flight will never be “routine” or “safe.” It’s as safe as NASA engineers can make it (although the next manned mission has several worrisome issues), but the idea that sitting on top of a vehicle powered by more than 5 million pounds of liquid hydrogen and oxygen, generating 7 million pounds of thrust, will ever be “routine” is delusional. The unforgiving environment of outer space will always make manned space flight dangerous and unpredictable.

However, so was a trip from St. Joseph, Mo., to Sacramento, Calif. in 1850. Eventually, we’ll develop the systems that will make space travel less risky for humans.

The new year promises to be one of the most pivotal in recent history. Midterm elections will determine if we continue to move forward or slide back into lawfare, impeachments, and the toleration of fraud.

PJ Media will give you all the information you need to understand the decisions that will be made this year. Insightful commentary and straight-on, no-BS news reporting have been our hallmarks since 2005.

Get 60% off your new VIP membership by using the code FIGHT. You won’t regret it.