If Ibn Khaldun parachuted into Washington in 2026, he wouldn’t ask for directions. He’d ask for a whiteboard.

The man spent the 14th century explaining why empires rise, rot, and fall apart under their own weight.

The awkward truth? His framework maps onto modern America a little too cleanly.

Debt binges. Bloated bureaucracies. Culture-war bread and circuses. Elites who talk about “the people” the way anthropologists talk about uncontacted tribes.

Different fashion. Same play.

Khaldun’s masterwork, the Muqaddimah, was an owner’s manual for civilization. But it came with a disclaimer explaining why the thing always breaks down after a few generations.

The One Idea That Explains Everything

Khaldun’s core concept is asabiyyah. It means social cohesion, shared purpose, or the willingness of a group to sacrifice for something bigger than itself. It’s the stuff that pushes people to build great things, as the “outsiders” topple the decadent elite and their older, worn-out model.

Khaldun argued empires don’t fall because barbarians get smarter. They fall because the mandarins grow fat and happy.

The pattern goes like this:

- A hard, cohesive group from the periphery takes over.

- They build institutions, win battles, and create wealth.

- Then comes comfort, entitlement, and the lawyers.

- Taxes rise, productivity sinks, elites detach.

- Finally, the state exists mainly to feed itself.

At that point, the empire doesn’t collapse — it metastasizes.

If that sounds suspiciously like a first draft of modern public choice theory, you’ve got an excellent nose for this stuff. Ibn Khaldun got there six centuries before Buchanan and Tullock.

Luxury As A Mindset

When Khaldun talks about luxury, he’s not talking about fine dining or yachts. He’s talking about a mentality shift.

Early rulers protect property because they need productive citizens. Think “A republic, if you can keep it.” Late-stage rulers extract because they feel entitled. That’s more like the populace figuring out it can vote itself money.

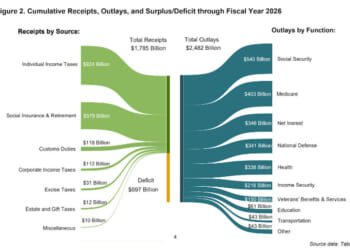

Spending expands. Payrolls swell. “Learing centers” multiply. The state invents new taxes, fees, compliance regimes, and “temporary emergency measures” that never expire, as Milton Friedman once warned us. Eventually, record tax revenues can’t keep up with unfunded liabilities and interest costs.

At that stage, high taxes no longer fund the empire. They quietly strangle it.

Sound familiar?

Add in a massive military and security apparatus that increasingly looks inward, and Khaldun would check every box on his imperial bingo card.

Asabiyyah, Ivy League Edition

Amazingly (or not), Khaldun also warned that elites eventually cluster in cities, intermarry socially, educate their children in the same schools, and lose contact with the conditions that forged their ancestors’ grit.

Washington, New York, Boston, and San Francisco may have different zip codes, but the same cocktail parties. It’s a narrow class recycling itself through Ivy League credentials, corporate boards, think tanks, NGOs, and regulatory agencies.

Meanwhile, large chunks of the country feel governed by people who don’t know them, don’t like them, and don’t particularly need them anymore.

When asabiyyah fades, politics stops being about shared goals and becomes a permanent cage match over status, symbols, and spoils.

This polarization is a hallmark of late-stage empire behavior.

The Barbarian Born Inside the Gates

Drop Donald Trump into this framework, and he stops looking like an anomaly and starts looking inevitable.

Trump certainly isn’t the cause of America’s decay. He’s a symptom with the loudest microphone in the highest office of the most powerful empire in human history.

He channels a kind of counter-asabiyyah, a coalition of people who no longer recognize the moral authority of the elites and are happy to throw bricks through its stained-glass norms.

Tariffs. Walls. “You’re getting ripped off.” It’s classic late-empire rhetoric.

To put it in Khaldun’s terms, Trump is what happens when the coastal cohesion cracks and a rival narrative forms in the flyover states.

But here’s the catch Khaldun would immediately spot: this isn’t a disciplined desert tribe bound by blood, hardship, and shared survival. It’s a media-age coalition glued together by rallies, memes, and shared enemies.

The energy is real, but the glue that holds the people together is thin. Exhibit A is how the Venezuela incursion split MAGA in two.

This makes Trumpism less the birth of a new dynasty and more a violent tremor inside an old dynasty.

Policy Irony

Khaldun insisted that stable rule depends on predictable law, secure property rights, and moderate taxation. Kill incentives, and you kill the state.

Modern America does the opposite, regardless of party. Tax cuts on one hand. Regulatory clubs and geopolitical theatrics, on the other hand.

The state grows, even though the Federal Register was slashed. The budget deficit grows even though it was supposed to be reduced. The money supply grows even though Candidate Trump asserted (correctly) that we were living in a false economy. But if anything, social cohesion has eroded further.

Everyone promises growth. No one rebuilds trust.

From a Khaldunian lens, that’s how you get endless motion without renewal, the so-called “hamster wheel empire.”

The 120-Year Clock (Not a Deadline, a Warning)

Khaldun suggested empires last about 120 years based on patterns he observed back in the 14th century. Apply it to America’s imperial phase, and you get dates that make people uncomfortable.

But empires don’t die on schedule. They stumble, improvise, and double down. Very rarely do they reset.

The loss of asabiyyah guarantees fragility, if not outright collapse—fragility to shocks, rivals, and self-inflicted policy disasters.

In that fragile space, Trump is both actor and mirror. His nationalism reflects an empire that no longer believes its own origin story. His theatrics reflect a political culture in which governing and entertainment have merged into one blurry spectacle.

To Ibn Khaldun, that fusion would be the tell. When sovereignty becomes performance, the serious work has already been deferred too long.

Wrap Up

Khaldun wasn’t a nihilist. He believed cycles could restart, cohesion could be rebuilt, and institutions could be re-founded on fairer rules.

But that requires sacrifice, limits, and shared purpose, not just louder rhetoric and better branding.

Whether America manages that reset, and whether Trump is remembered as a catalyst or a caricature, is precisely the kind of question the old Maghrebi historian would have loved.

He’d probably just sigh first.

Then he’d reach for the whiteboard.